When you watch a movie, the camera is doing a lot more than just recording the actors. It’s actually telling the story alongside them. By changing how close the camera is, what angle it's at, or what lens is being used, a director can change your mood without you even realizing it. Here is a breakdown of the basic tools filmmakers use to pull you into the story. Today We’ll be looking at Camera Distance, Camera Angle, and Camera Lens.

Finding the Right Distance

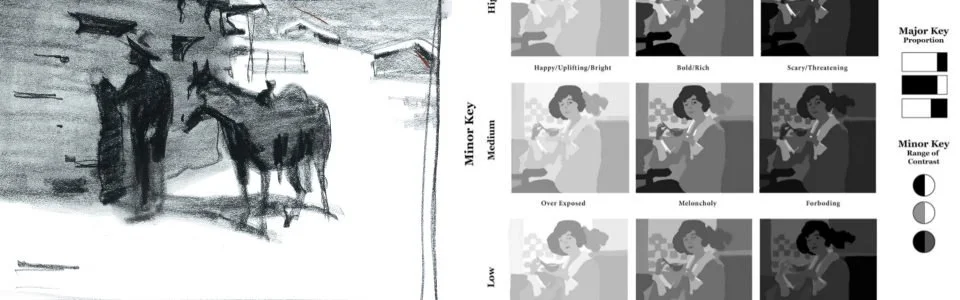

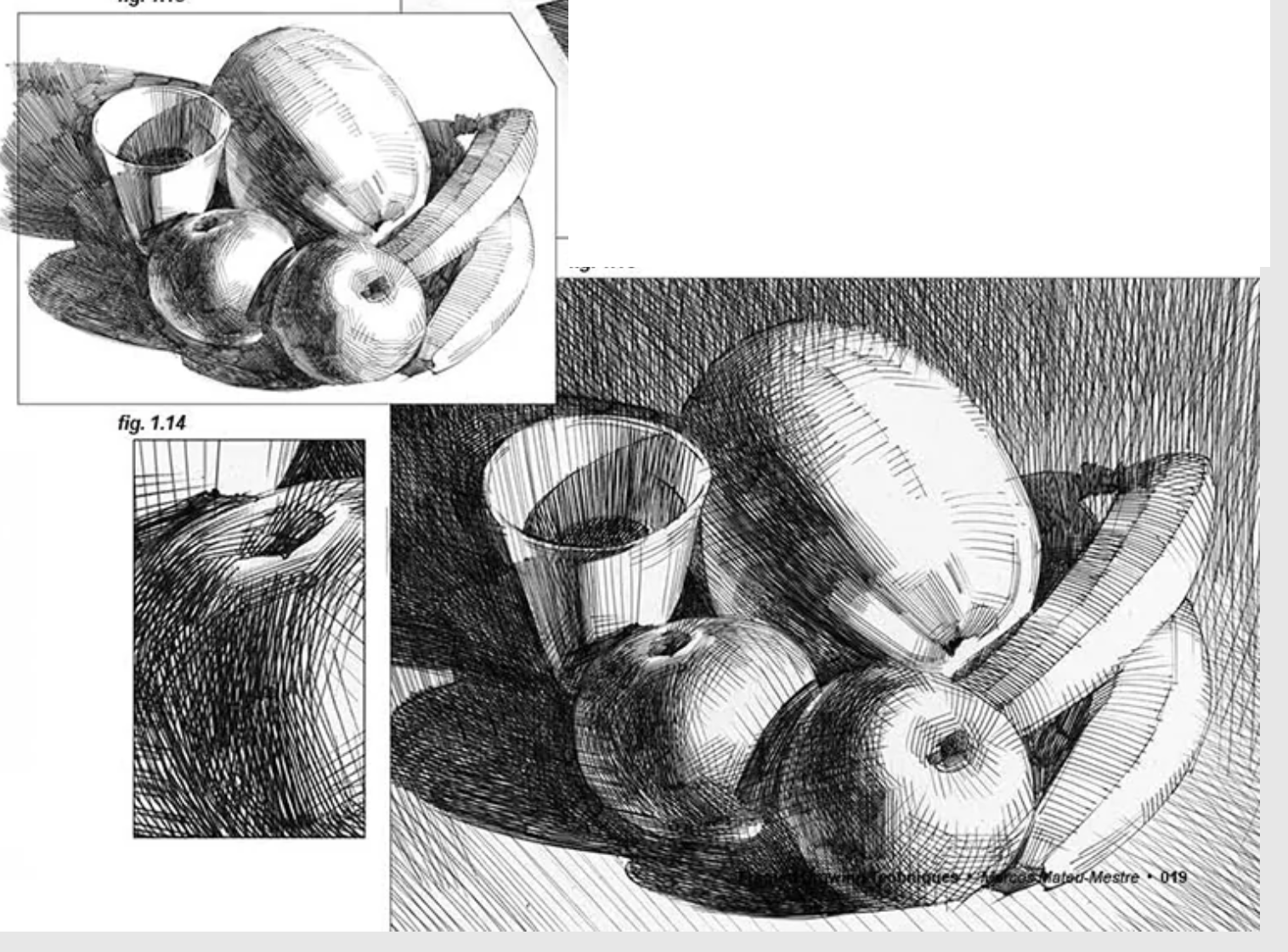

Mateu-Mestre, Marcos. Framed Ink: Drawing and Composition for Visual Storytellers. Design Studio Press, 2010. https://amzn.to/4rilAAp

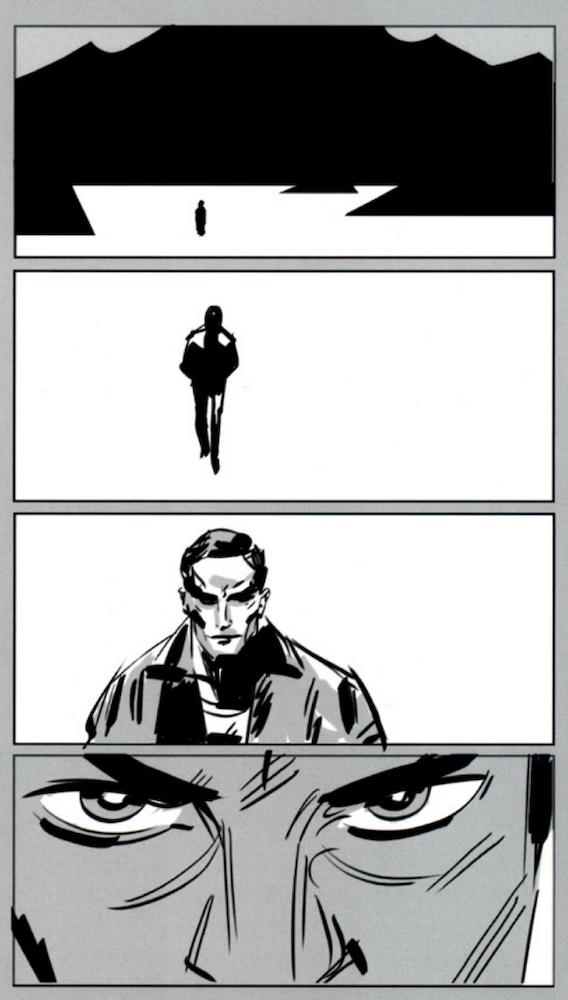

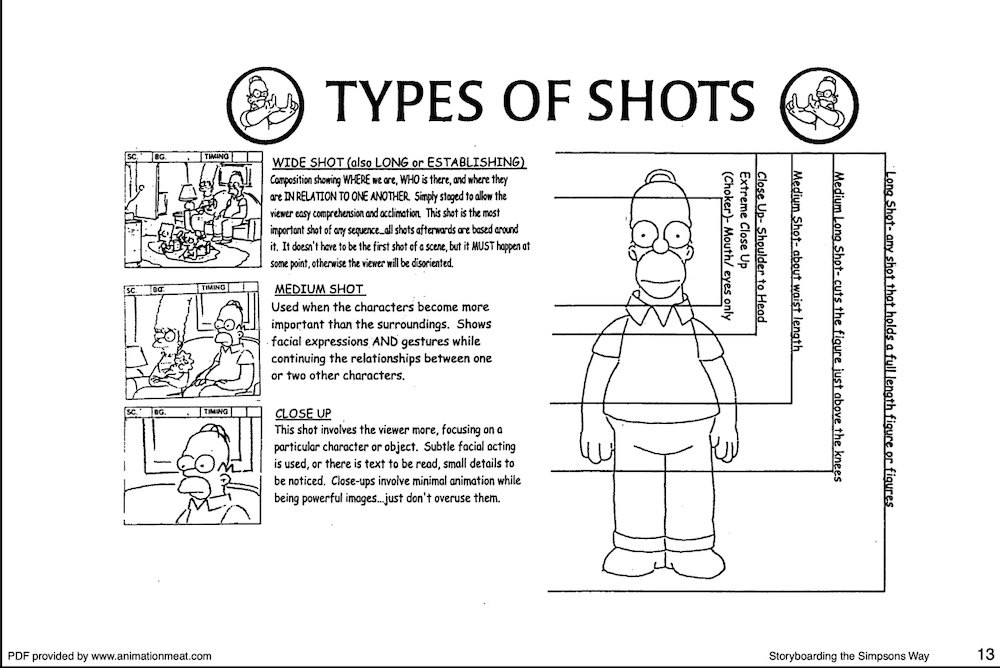

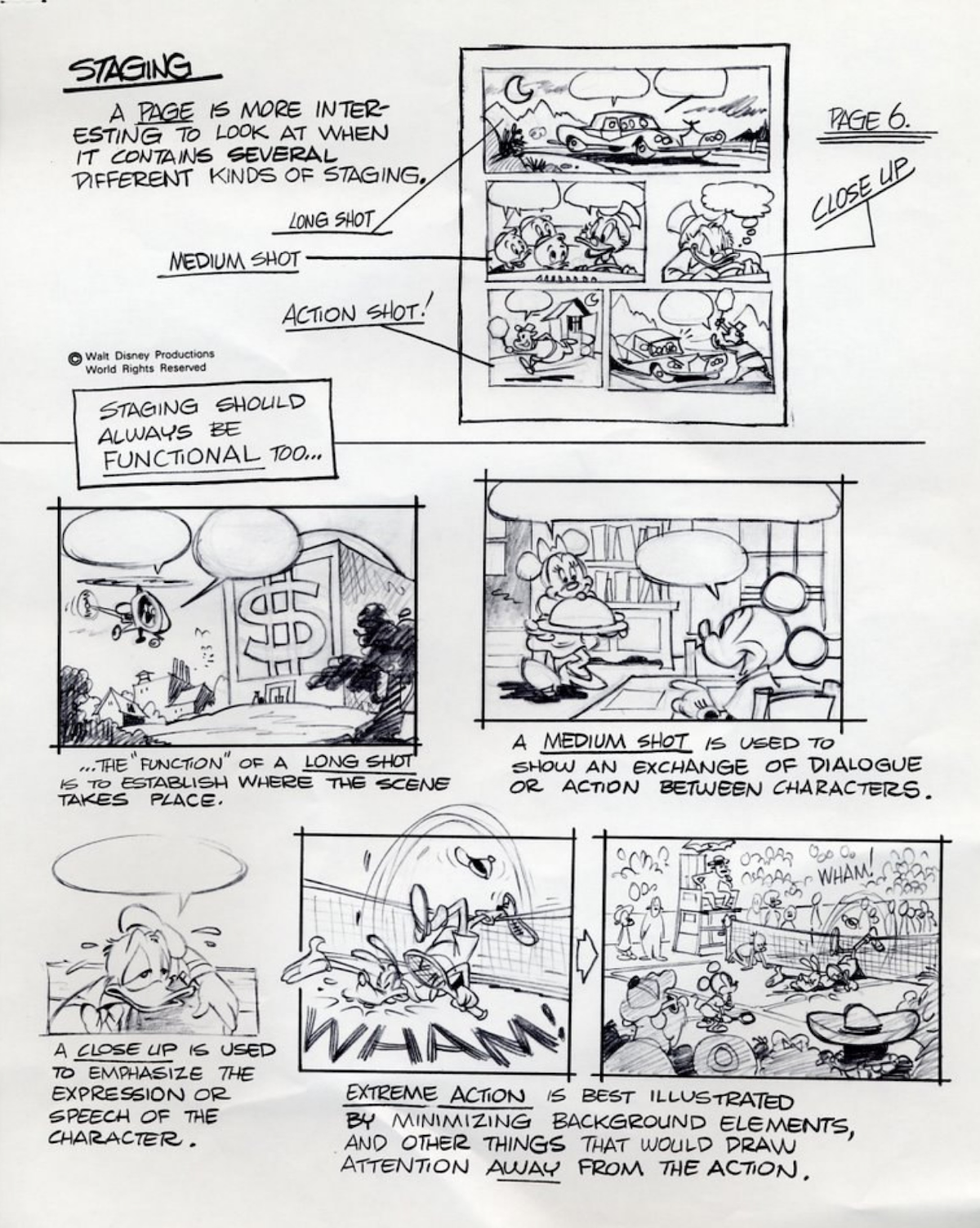

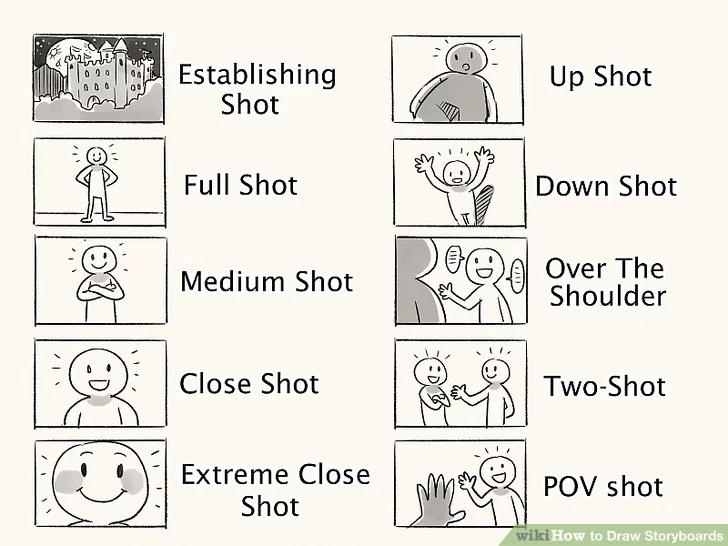

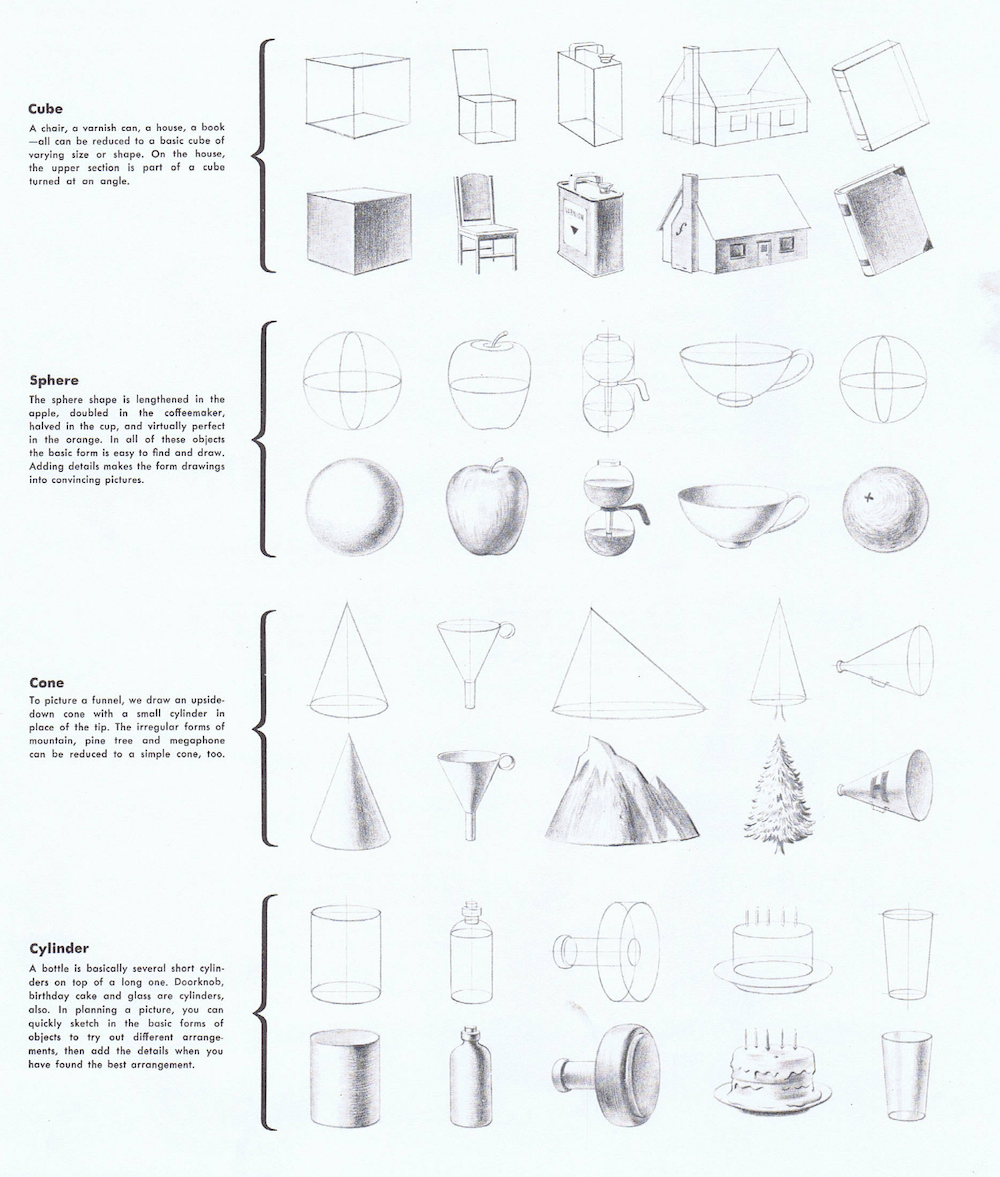

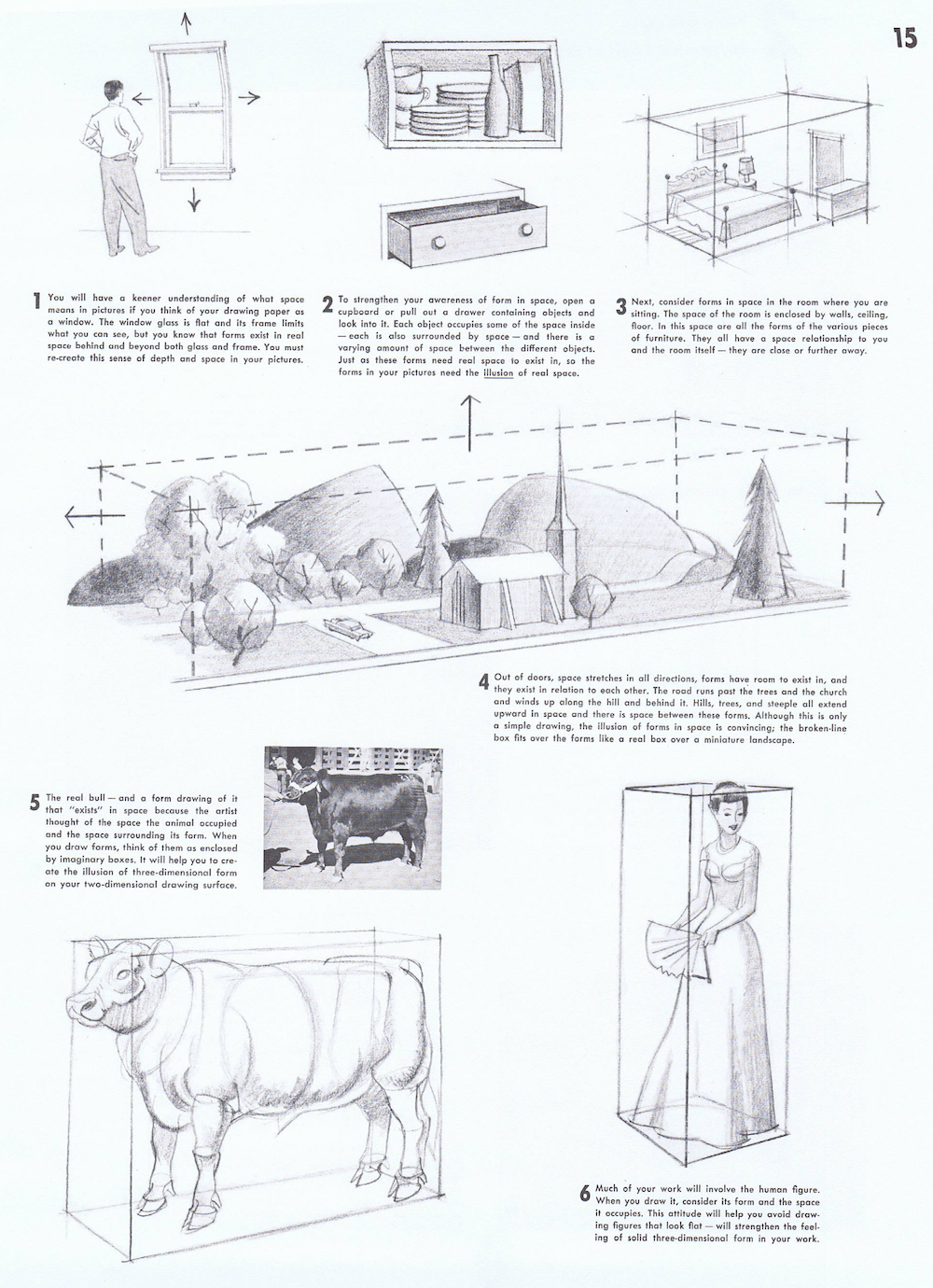

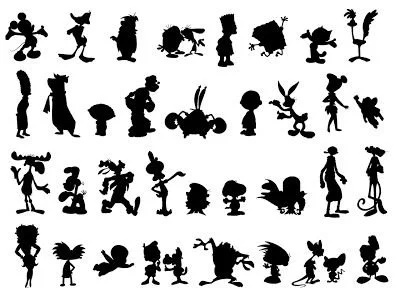

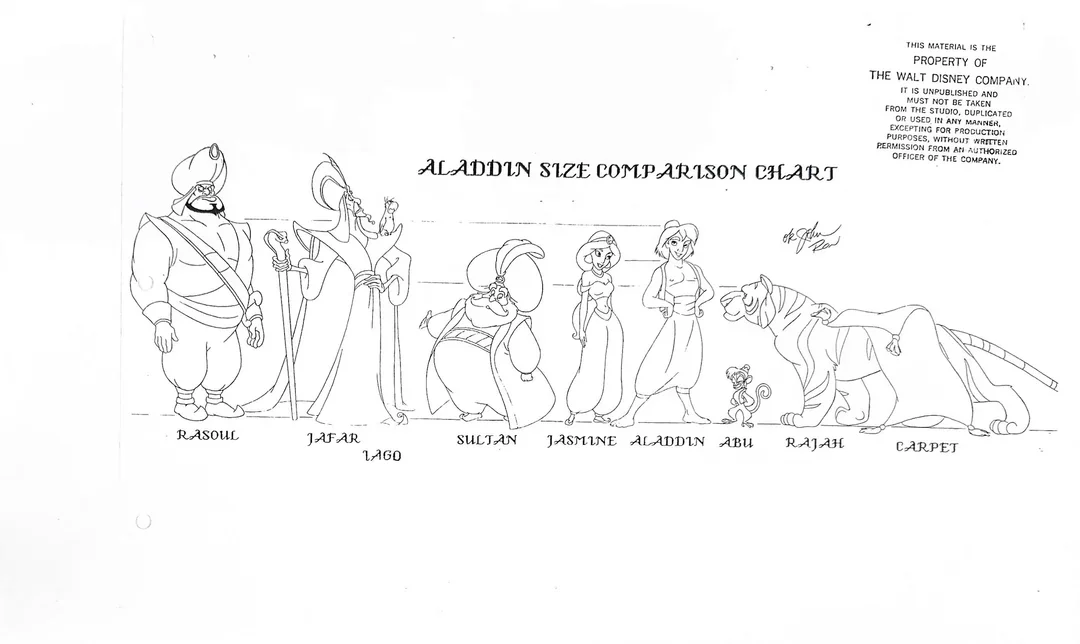

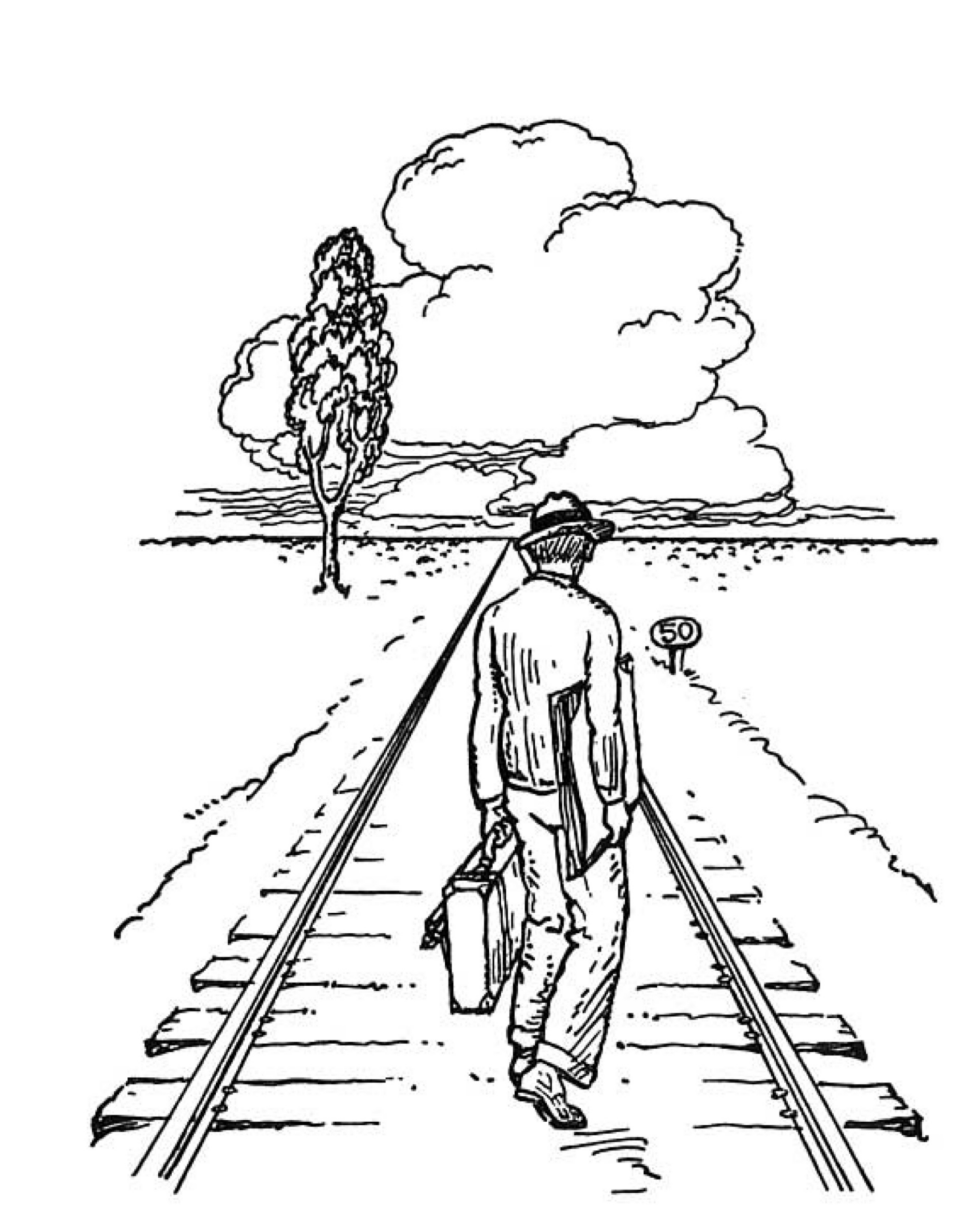

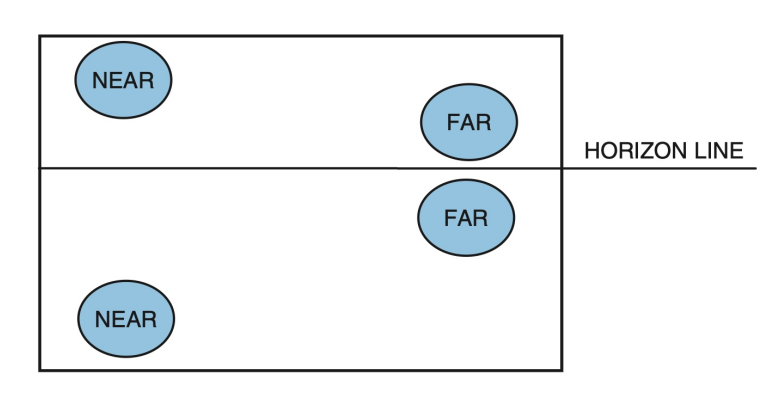

The distance of a shot tells you how to feel about a character’s situation. A Long Shot shows the whole body and the surrounding area. Think of a cowboy, Jean Giraud’s Blueberry, riding across a massive desert. It’s used to show how big the world is and how small the character feels. As the camera moves in for a Medium Shot (waist-up), the focus shifts to the conversation. This is the "comfort zone" of a movie, where most of the talking happens. When things get intense, the camera moves into a Close-Up, focusing only on the face. This is where you see the sweat on a hero's brow or the tears in a character's eyes, forcing you to feel exactly what they feel.

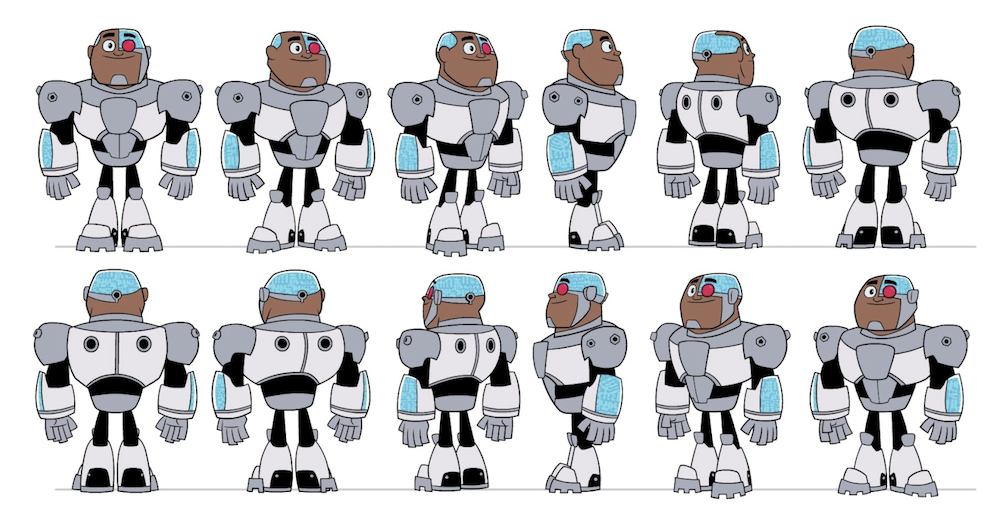

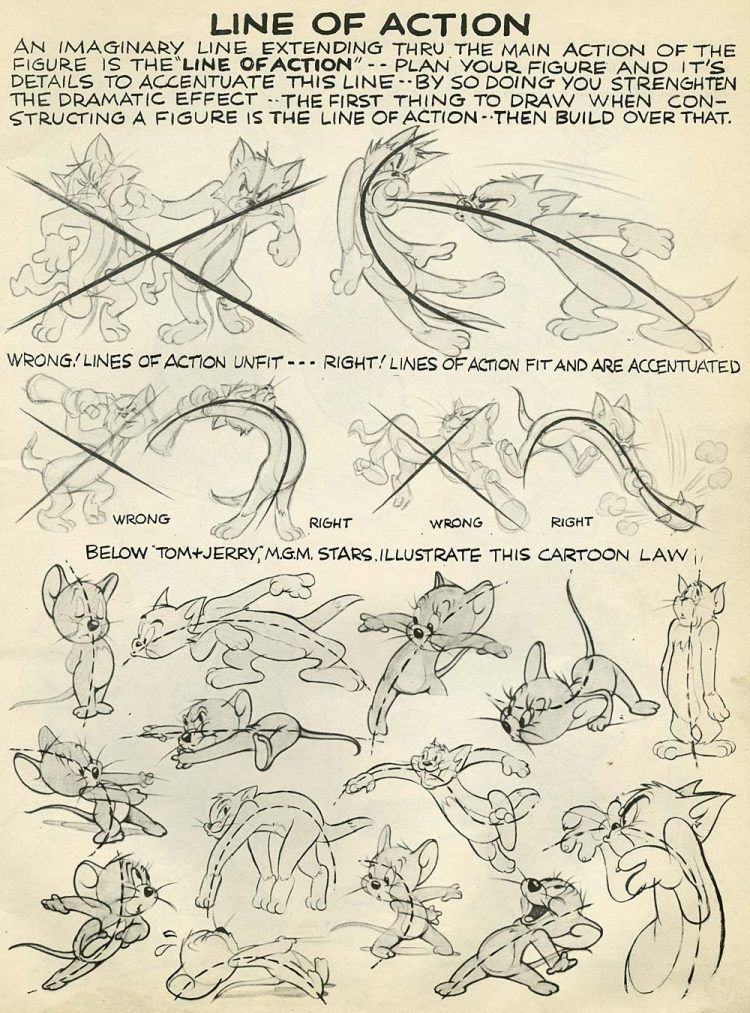

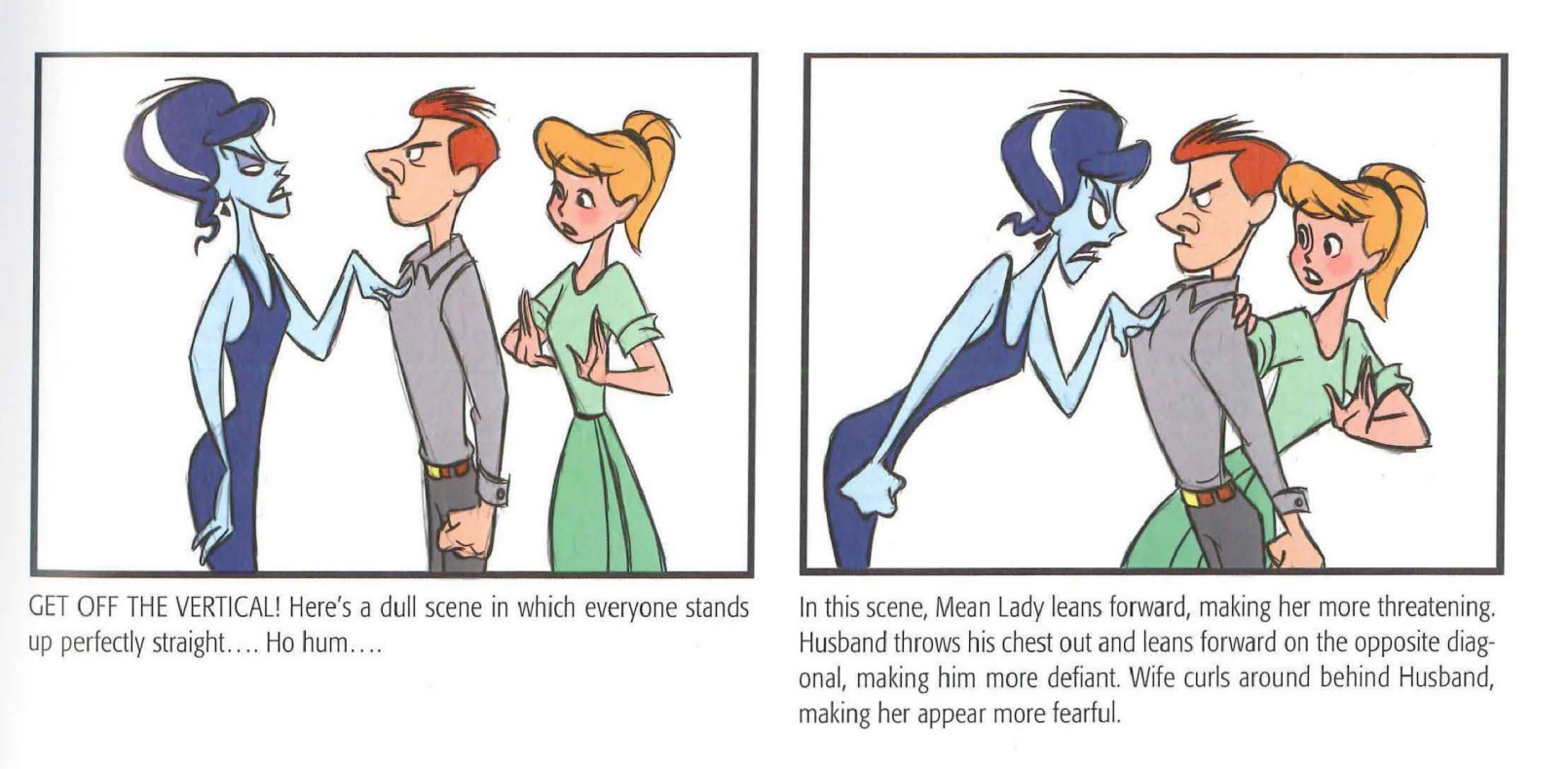

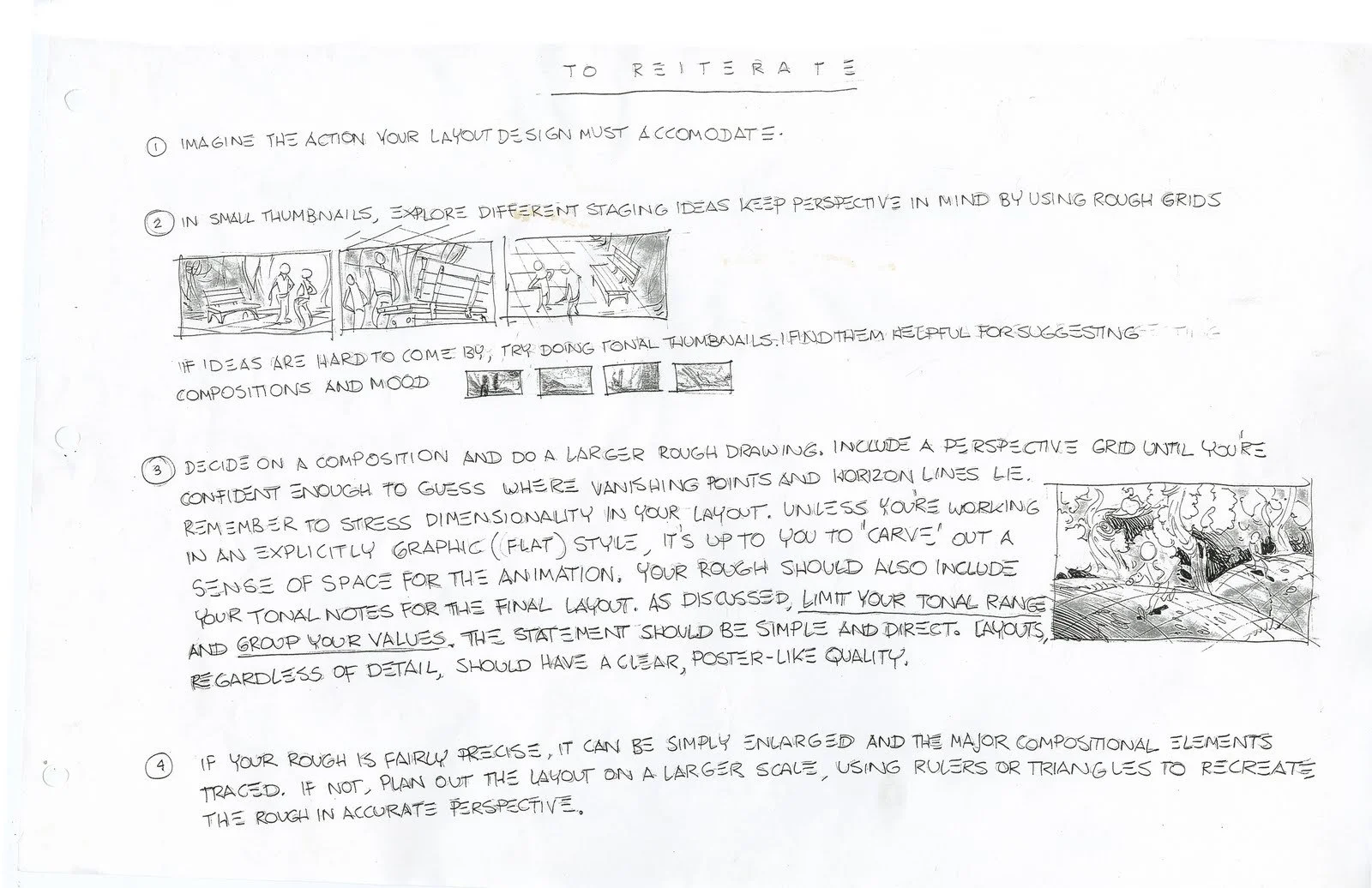

StoryBoarding the Simpsons way- http://Animationmeat.com

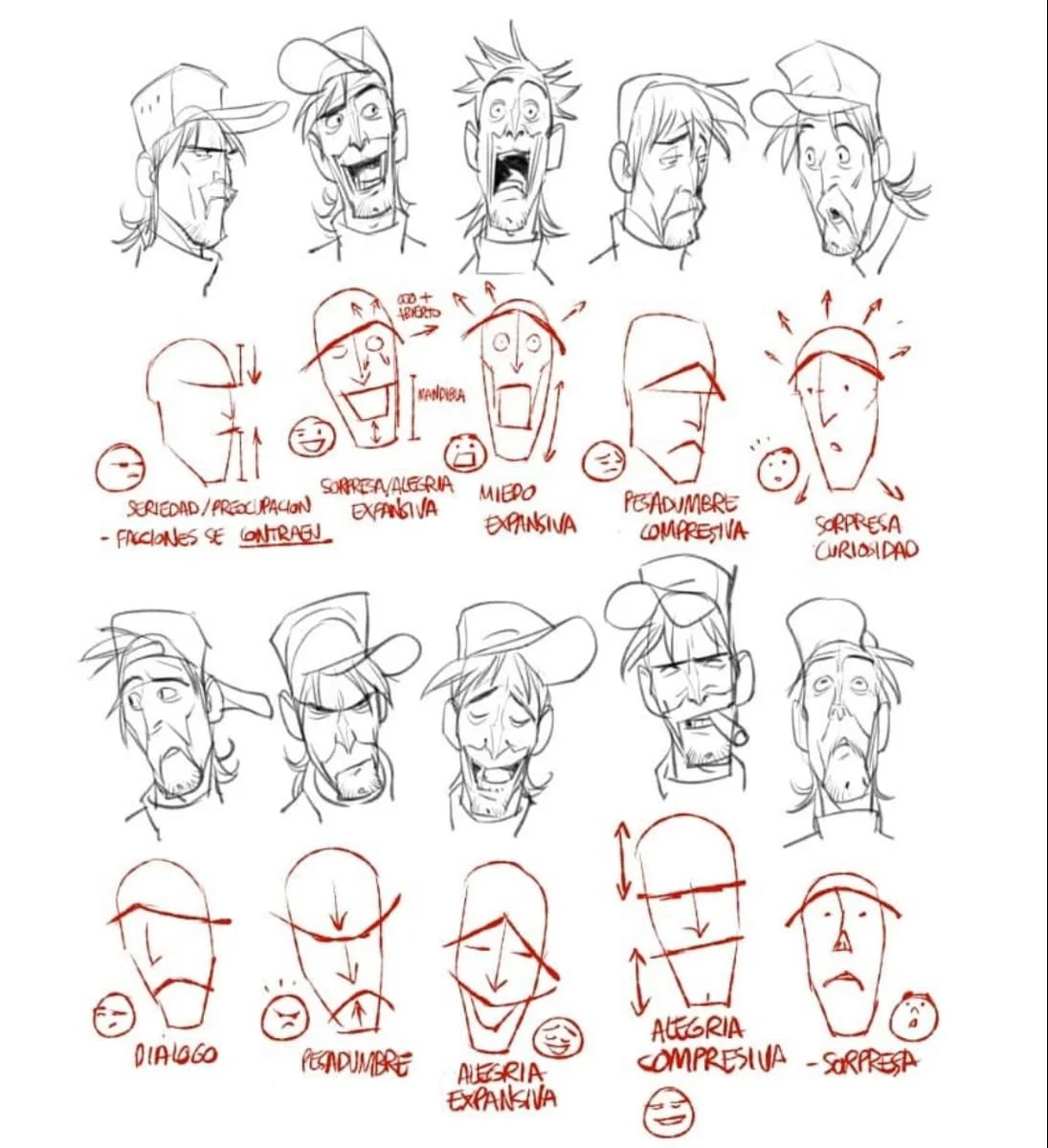

Using Angles to Show Power

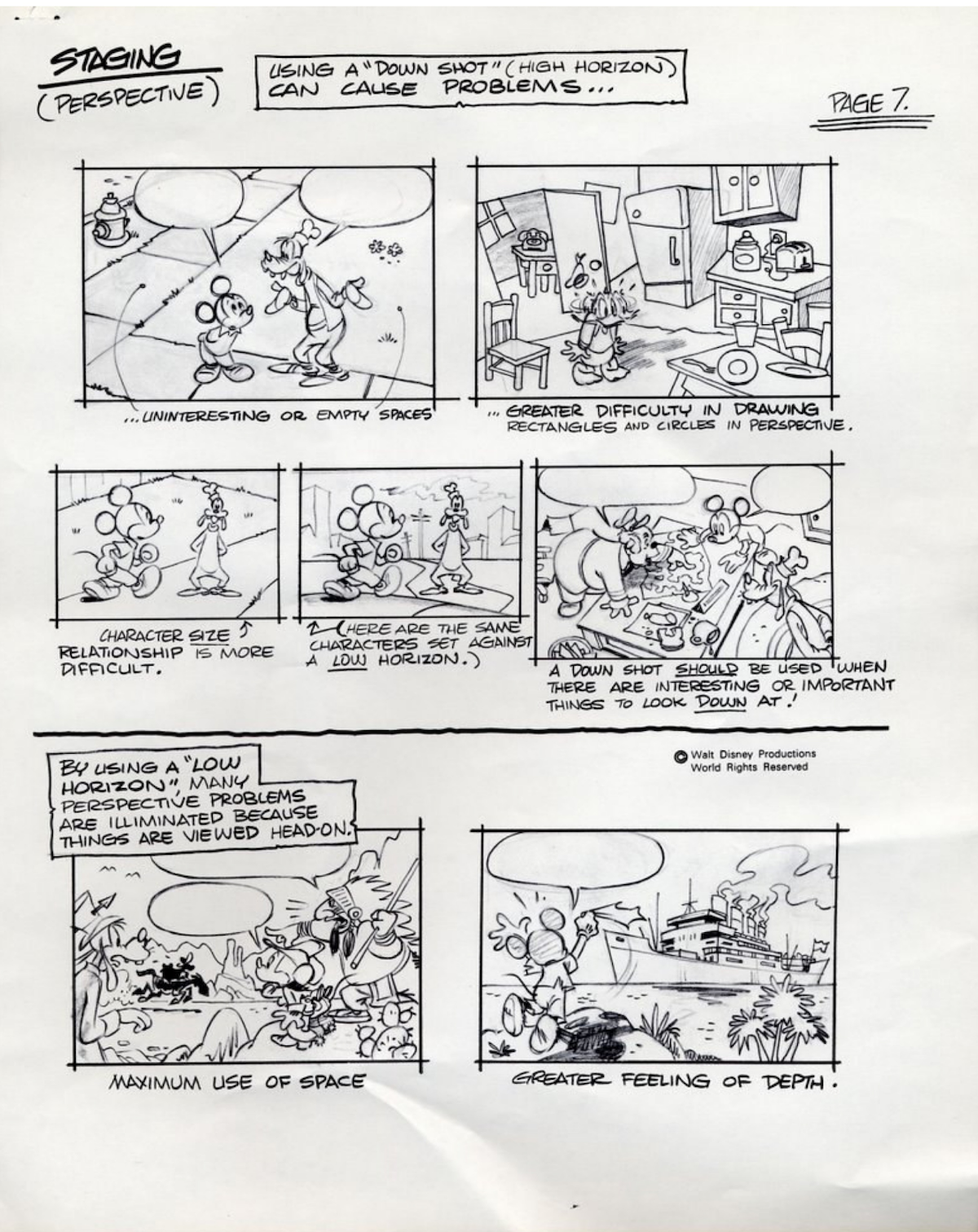

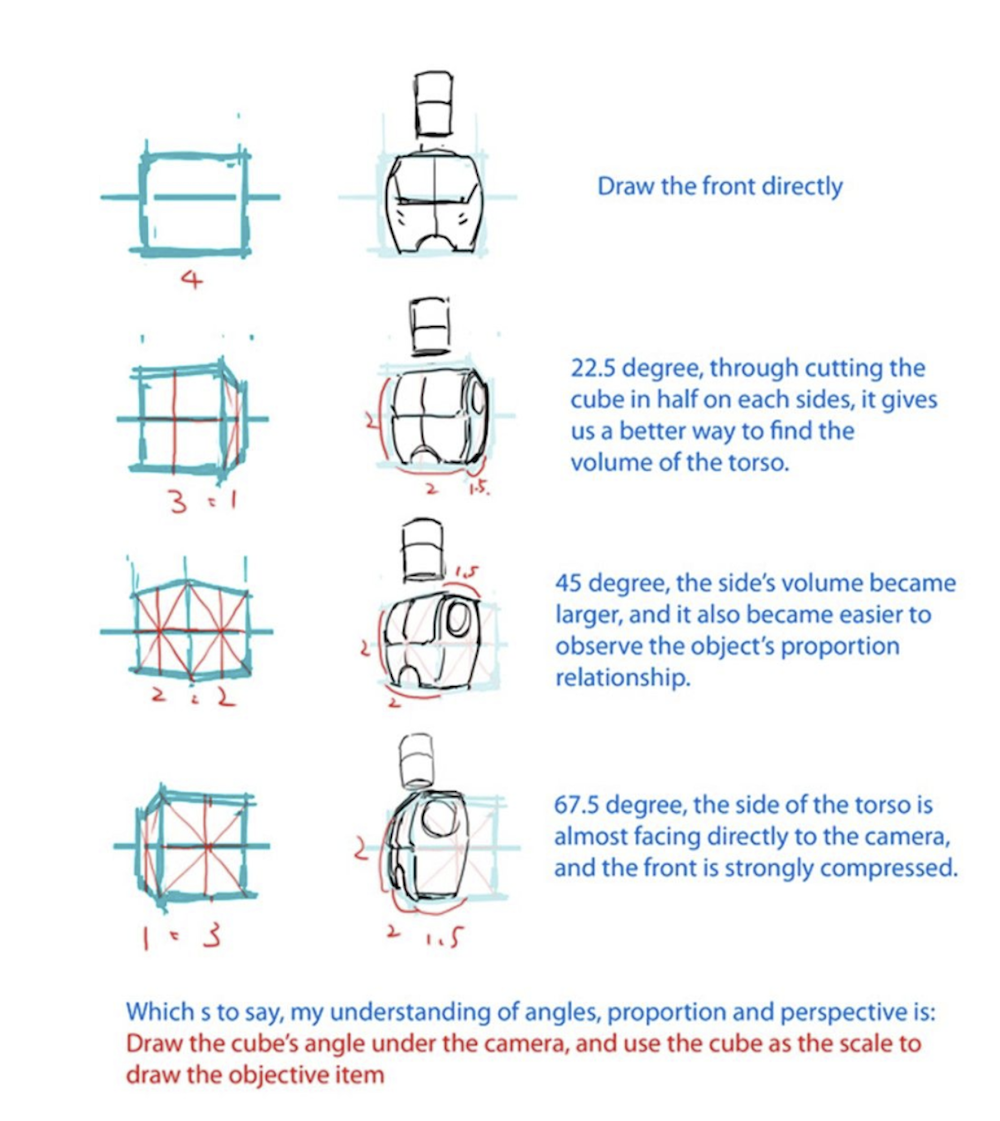

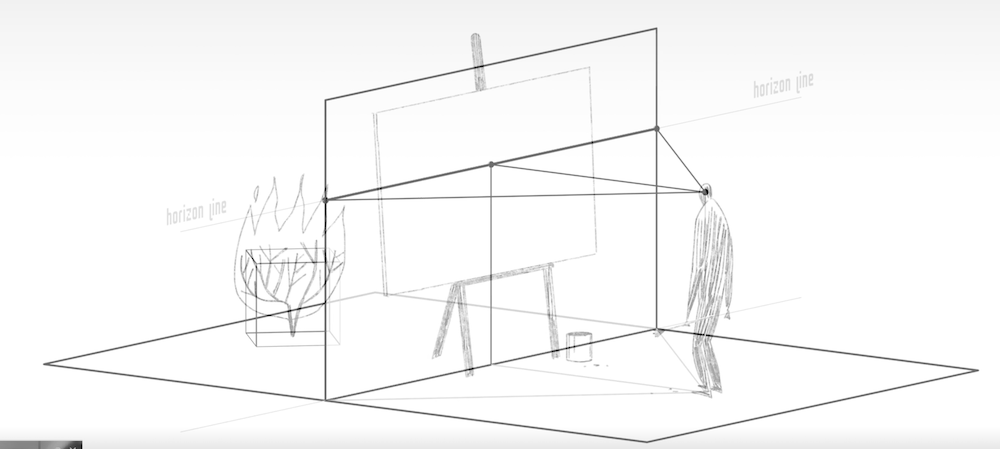

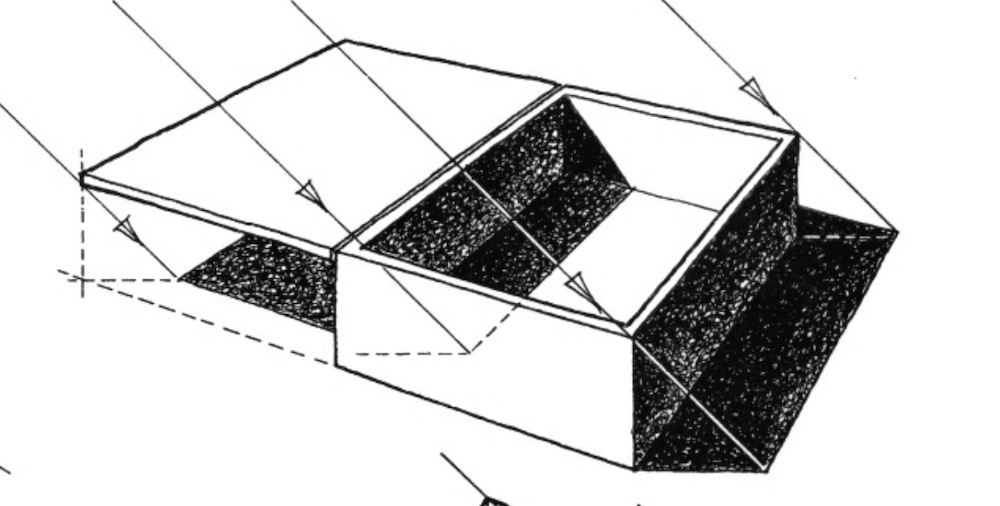

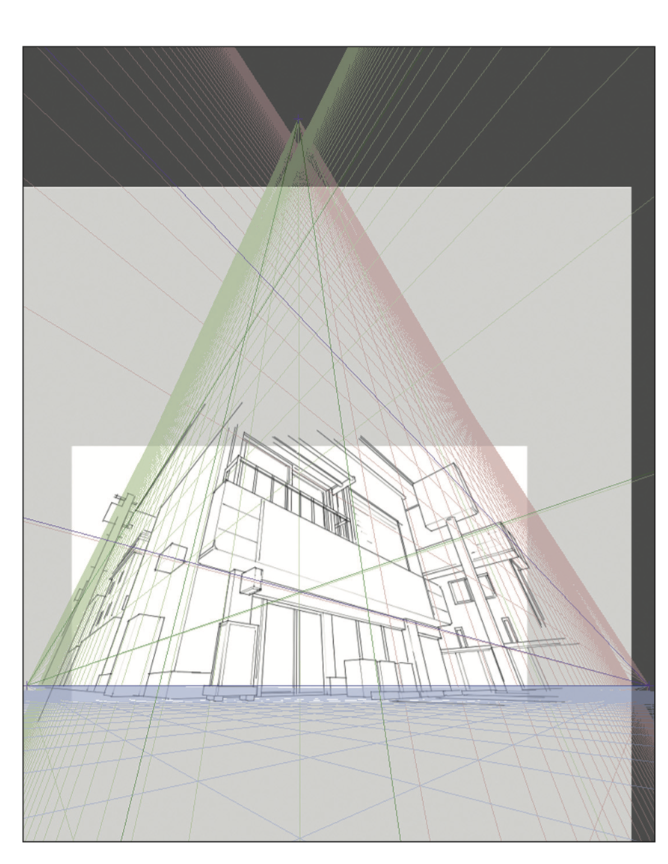

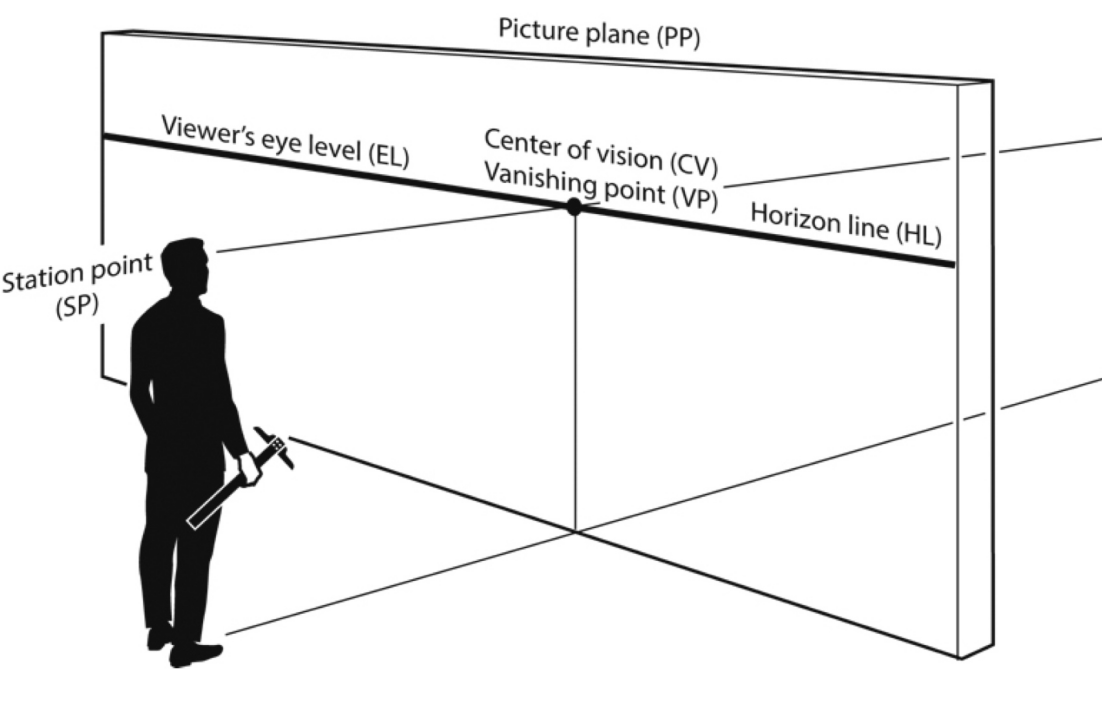

The height of the camera tells the audience who is in charge. If the camera is at Eye-Level, you feel like you’re just a person standing in the room. But if the camera looks up from a Low Angle, the person on screen looks huge and powerful. This is how directors make superheroes look legendary or villains look scary. On the flip side, a High Angle looks down at a character, making them look weak or trapped. For something more extreme, a Bird’s Eye View looks straight down from the sky to show a whole city or a crime scene, while a Dutch Tilt (tilting the camera to the side) makes the world look crooked and "off," usually to show that a character is losing their mind or in danger.

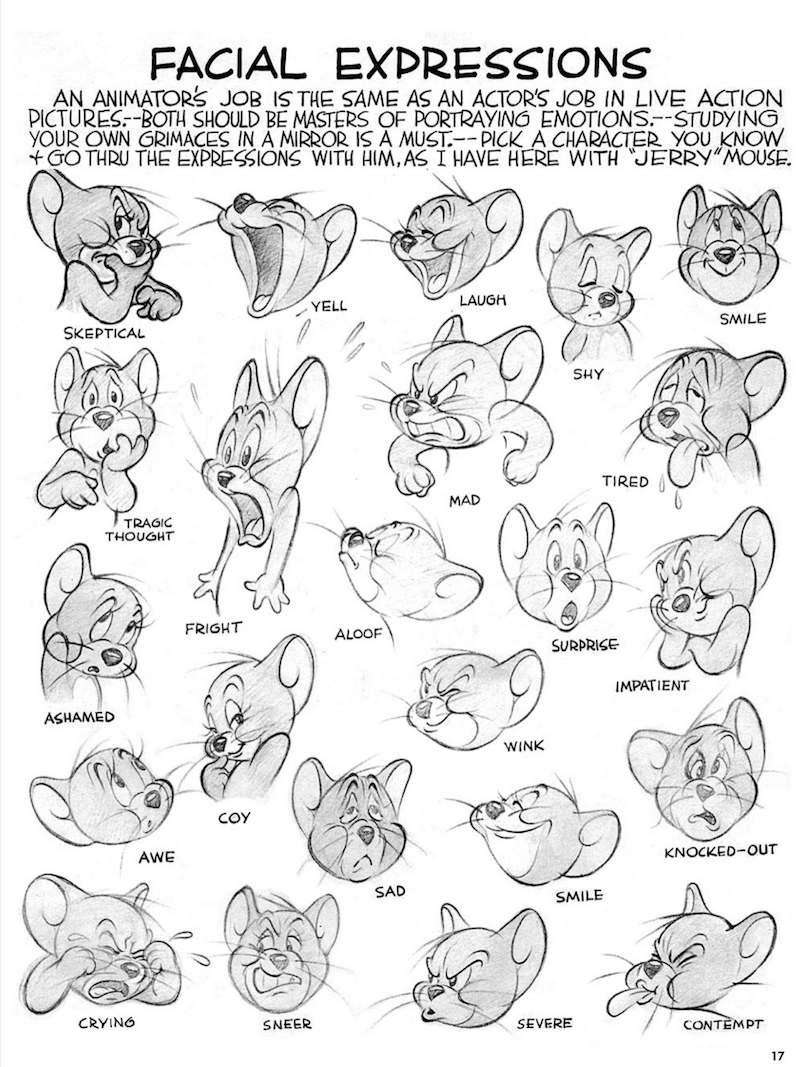

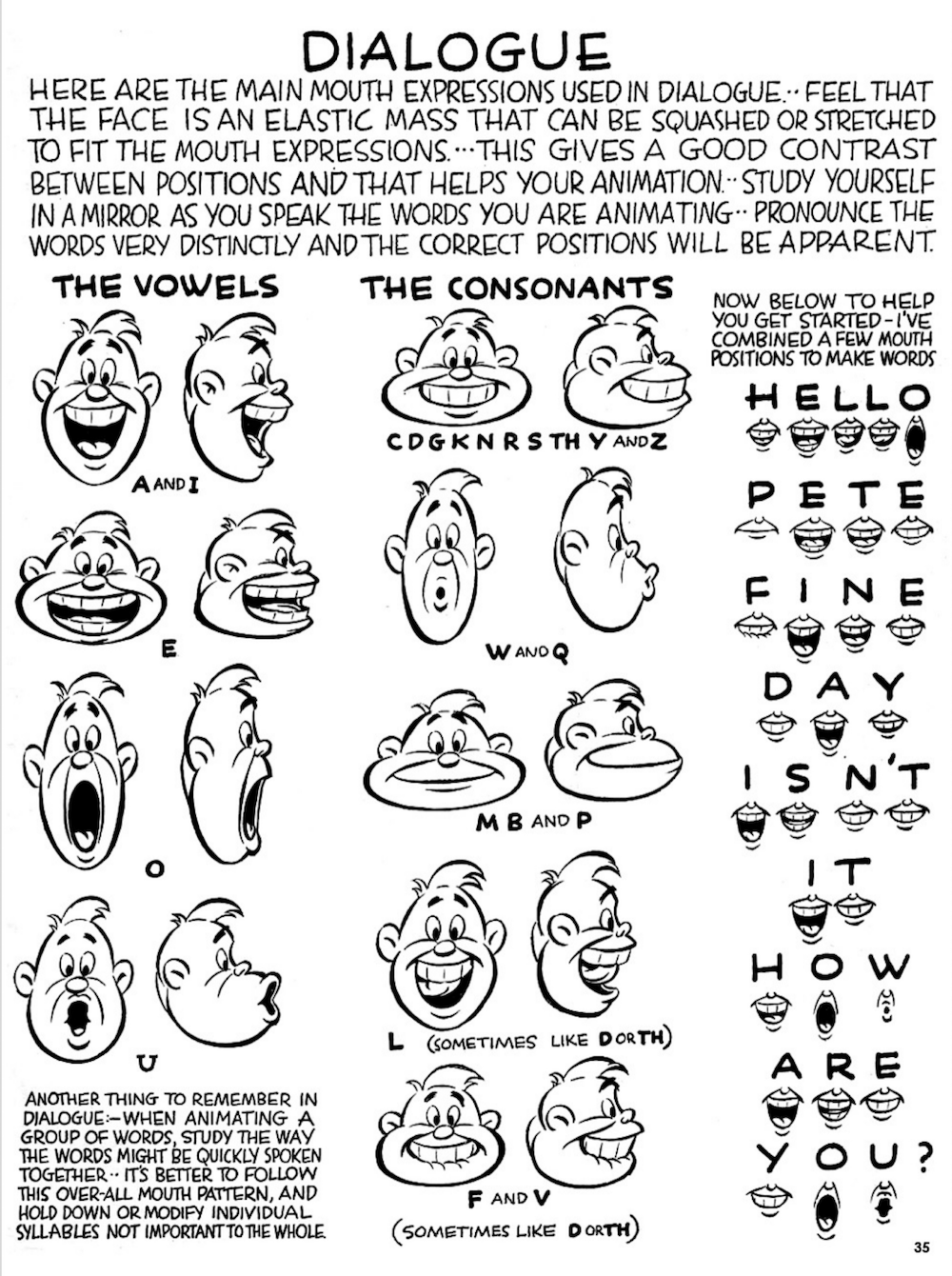

“Comic Strip Artist’s Kit (Redux).” Temple of the Seven Golden Camels, 2006, http://sevencamels.blogspot.com/2006/09/comic-strip-artists-kit-redux.html.

“Comic Strip Artist’s Kit (Redux).” Temple of the Seven Golden Camels, 2006, http://sevencamels.blogspot.com/2006/09/comic-strip-artists-kit-redux.html.

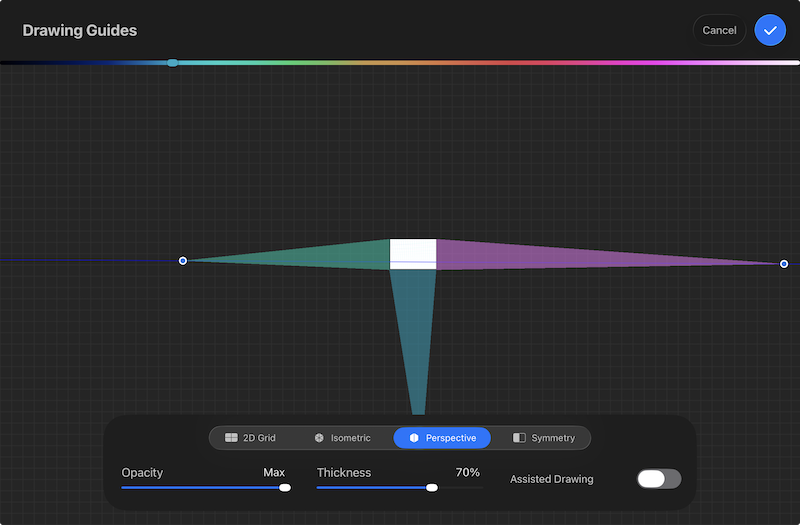

How Lenses Change the World

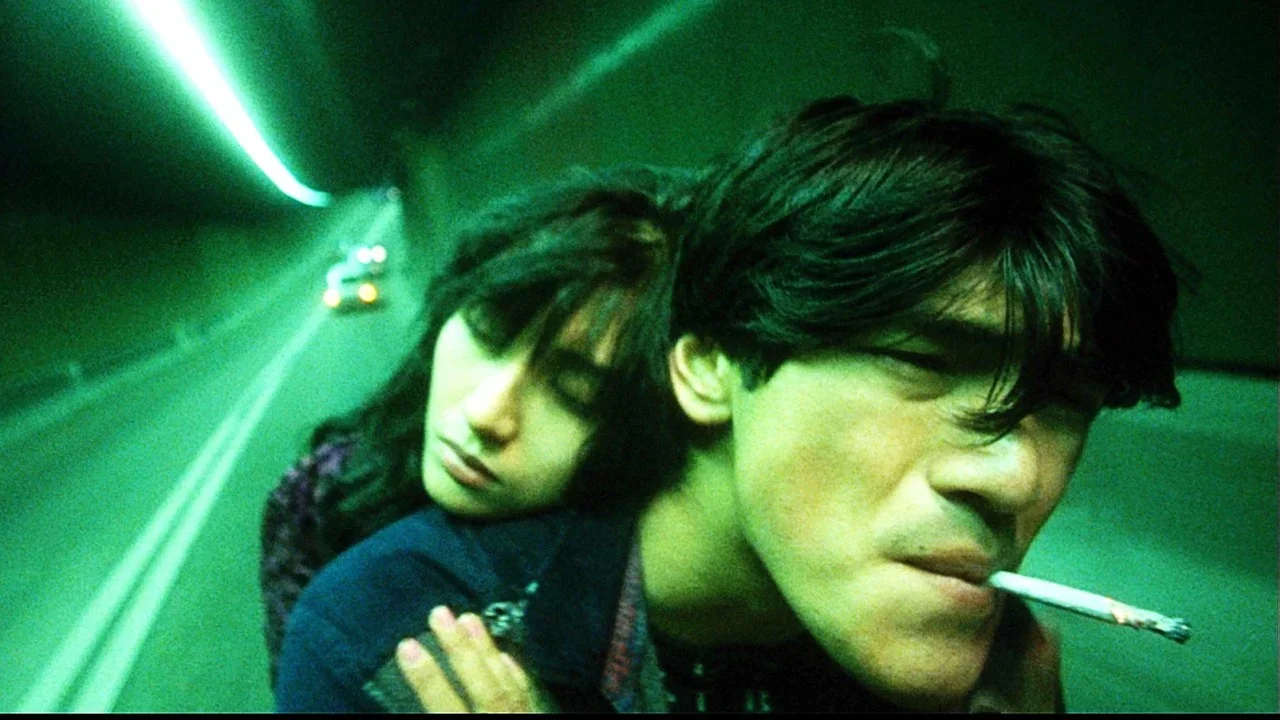

Wong Kar-wai’s Fallen Angels. Wong Kar-Wai uses the wide angle lens in unique and creative ways. https://amzn.to/4avOmpL

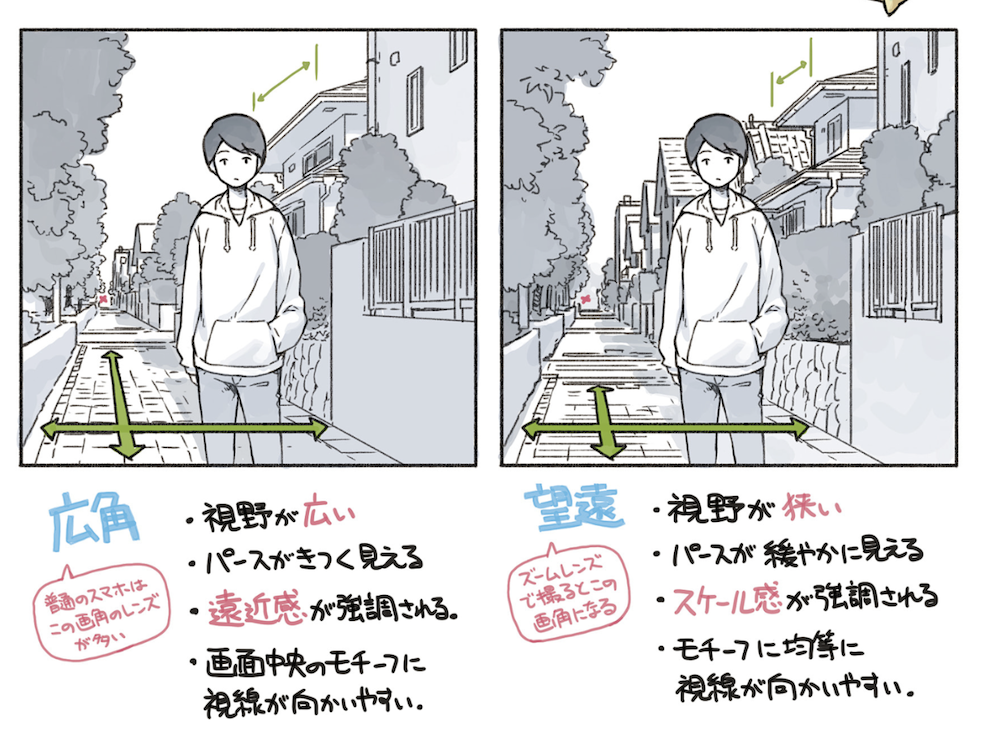

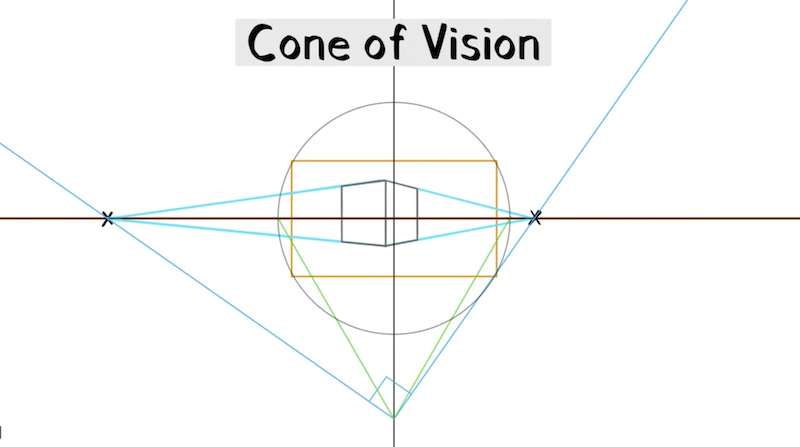

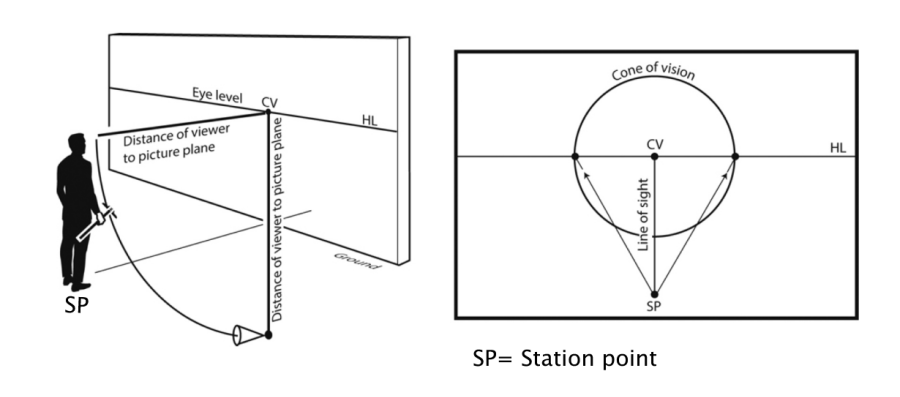

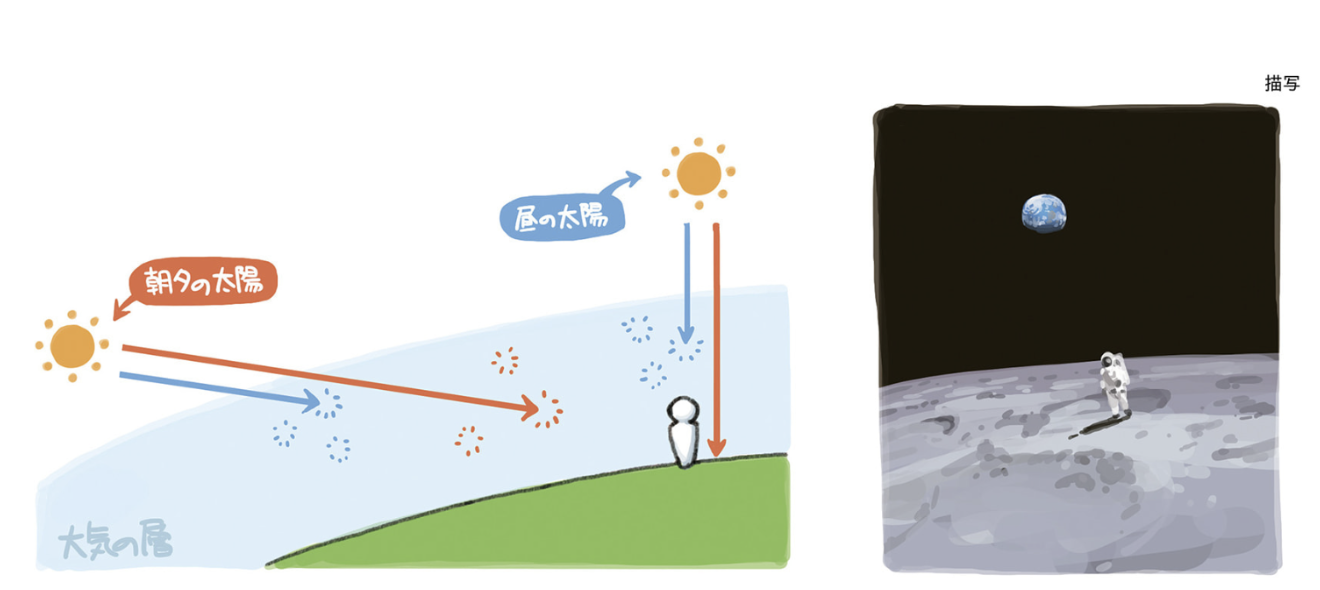

Different glass lenses change how we see space and distance. A Wide-Angle Lens sees a lot of the room at once but can make things look slightly stretched out. It’s great for a high-speed car chase or showing off a beautiful castle.

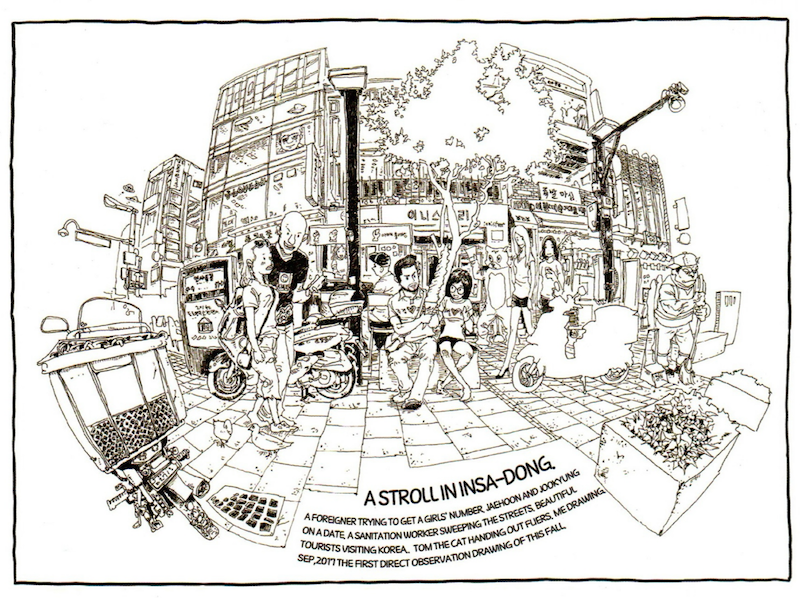

If you go even wider with a Fisheye Lens, the edges of the screen start to curve like a ball, which creates a trippy, distorted look often used in music videos or dream scenes.

On the other hand, a Telephoto Lens acts like a telescope. it zooms in on a subject and "squished" everything together the person. This removes a lot of the distortion that happens in the wide angles lens. This is why fashion photography uses more telephoto lenses.

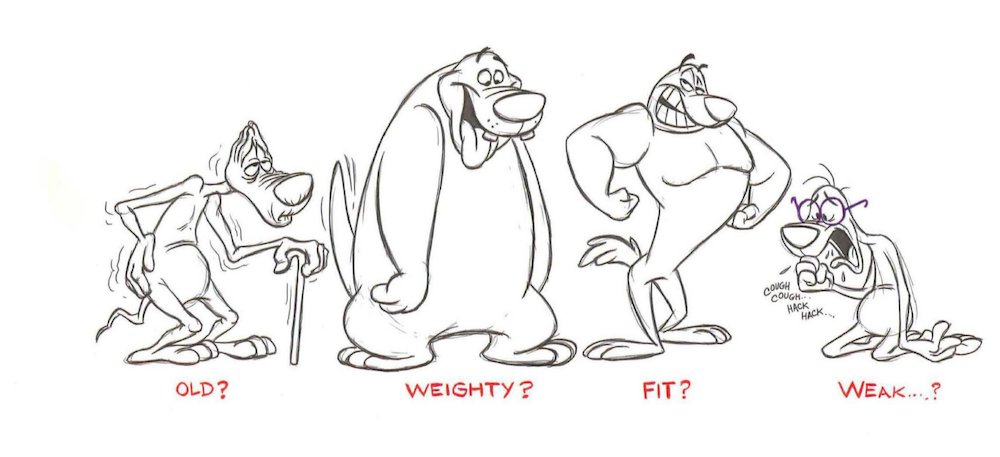

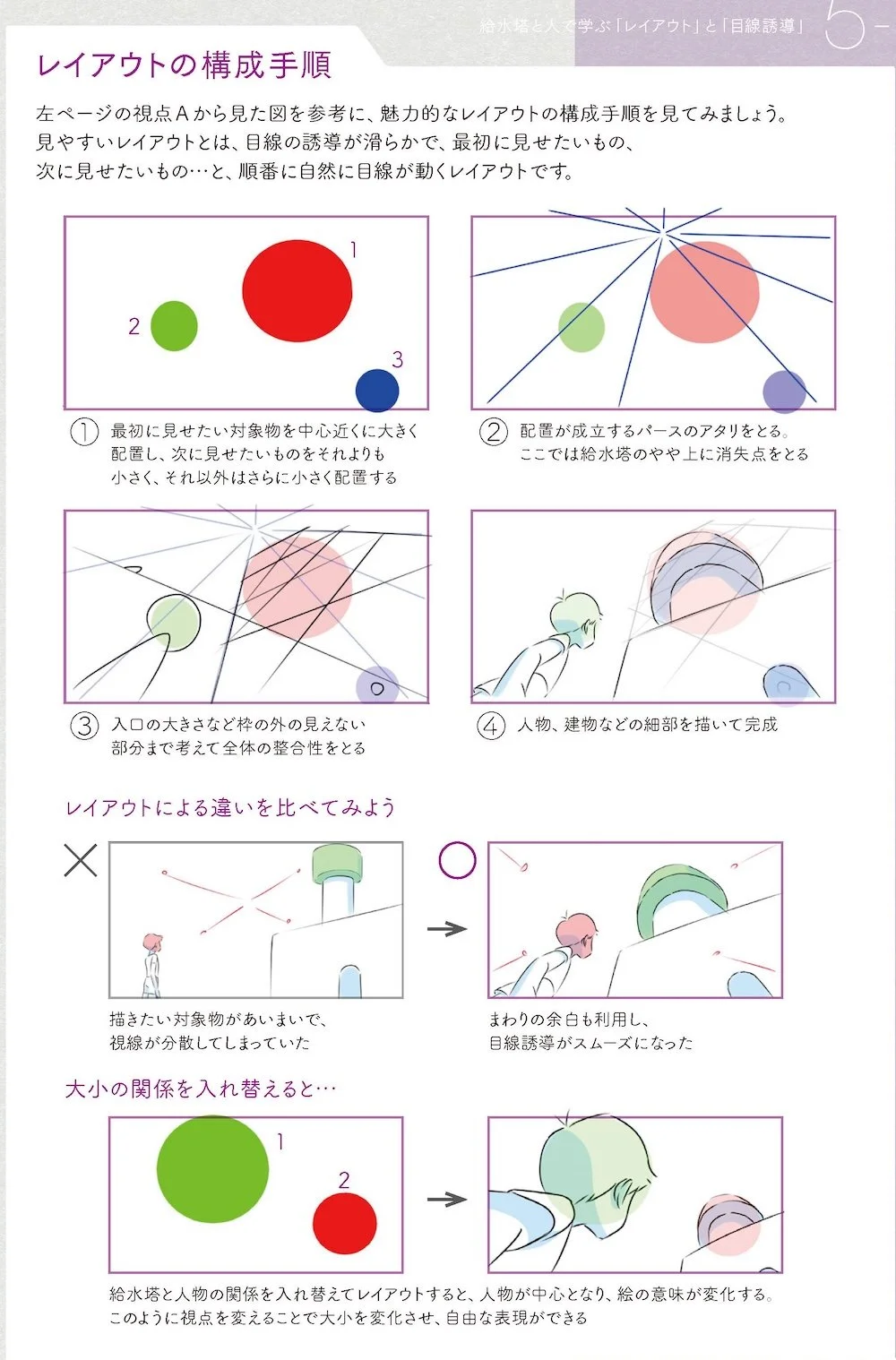

Yoshida, Seiji. TIPS! 絵が描きたくなるヒント集〈ダウンロード特典あり〉 [Tips! Hints to Make You Want to Draw]. MdN Corporation, 2023. https://amzn.to/4kEasv2

Page, Travis. “3 Ways to Draw Storyboards.” wikiHow, 24 Feb. 2025, www.wikihow.com/Draw-Storyboards. Fantastic reference to start thing about shots.