Drawing is fundamental to being human. I’ve never to meet a child who didn’t instinctively love making marks or drawing. While the barrier to entry is as low as a pencil and a scrap of paper, the actual power of drawing is vast.

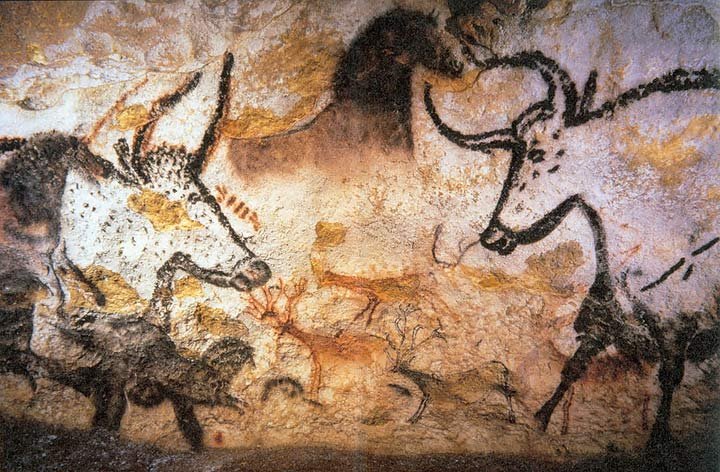

A glimpse into the past: The Great Hall of the Bulls in the Lascaux caves, France. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lascaux#/media/File:Lascaux_painting.jpg

To understand its potential, look at the cave walls of Lascaux. Those drawings were made thousands of years ago, yet the representation is so clear we can’t help but feel an immediate connection to our ancestors. Drawing is, in many ways, a form of magic. It is the ultimate blueprint for human innovation. Every blueprint for a cathedral, every CAD drawing for a product, and every tangible thought began as a drawing on a page. It is THOUGHT given form before it becomes MATERIAL.

This is where drawing finds its most practical power: it allows us to share the unshareable. When words fail to describe the specific curvature of a car or a complex idea, the drawing speaks. It acts as a universal translator, bypassing language barriers and connecting one mind to another through simple mark making.

The First Element: The Invention of the Line

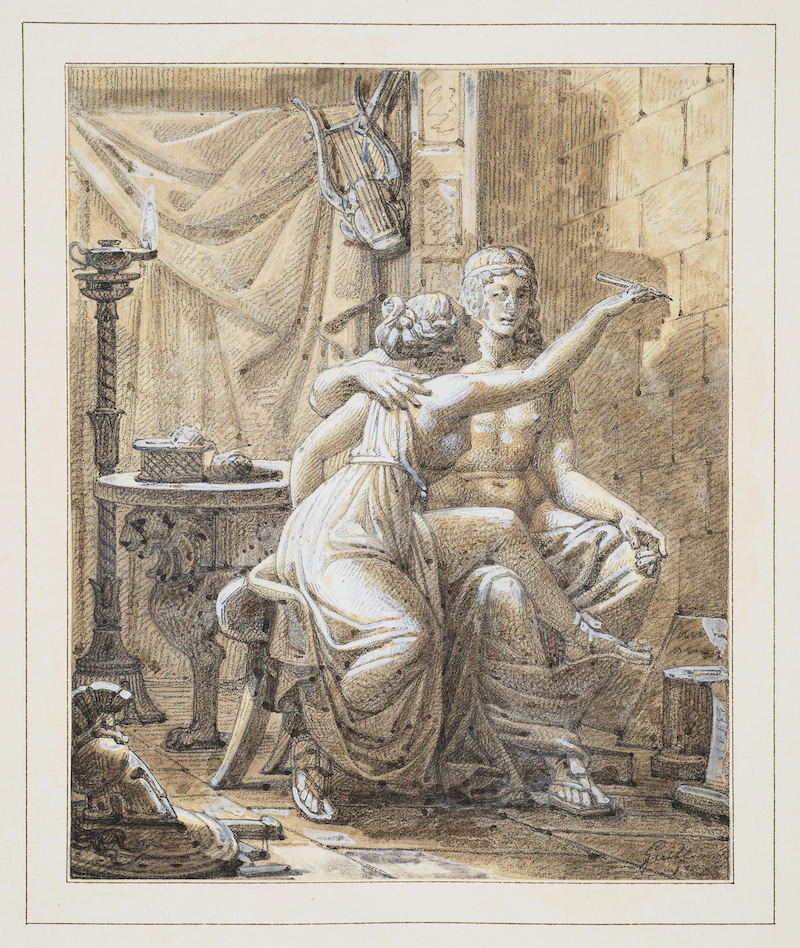

Alexandre-Charles Guillemot, The Myth of Dibutade or the Invention of Drawing, 1825.

We can’t pinpoint exactly when humans developed the concept of a "line," but history is full of legends about its origin. The Roman author Pliny the Elder tells a story of a potter’s daughter in Corinth. Her lover was leaving for a journey, and she couldn't bear to let him go without capturing his likeness. As lamplight cast his shadow on the wall, she traced the outline, preserving his silhouette in a single, unbroken line.

While we now have evidence of even earlier drawings in caves, the concept remains the same, the line is our most basic tool, yet it possesses infinite possibilities.

The Paradox of the Line

The use of line is intuitive. Give a toddler a crayon, and they’ll instinctively produce scribbles. As we grow, we use these marks to map our understanding of the world. However, there is a curious paradox. In the physical world, lines don’t actually exist. We don’t see black outlines around trees or people. Instead, we perceive edges, where one shape meets another, or where light meets shadow. The line is a uniquely human invention, a system of representation we created to impose order on visual reality.

What a Line Can Do

The Metropolitan Museum o f Art, New York

Van Gogh Museum,

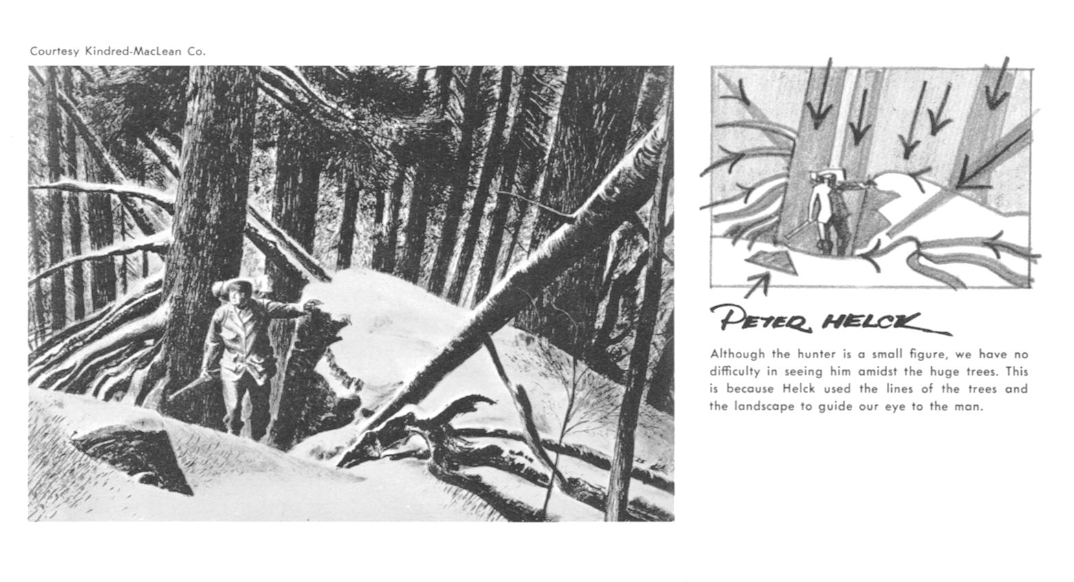

A line is more than just a mark; it is a vehicle for information. It has the power to define edges, distinguishing an object from the space around it. It can direct the eye, creating pathways that lead the viewer’s gaze through a composition. Line also expresses texture, using scratchy or rhythmic marks to suggest surface quality, and it suggests volume by using varying thickness to imply weight, shadow, and depth. It is the foundation upon which all design and forms are built.

Famous Artists Schools. Famous Artists Course: Lesson 3, Composition. Famous Artists Schools Inc., 1960.

Line Quality: The Artist’s Vocabulary

Huston, Steve. Figure Drawing for Artists: Making Every Mark Count. Rockport Publishers, 2016. https://amzn.to/3LKyTdg

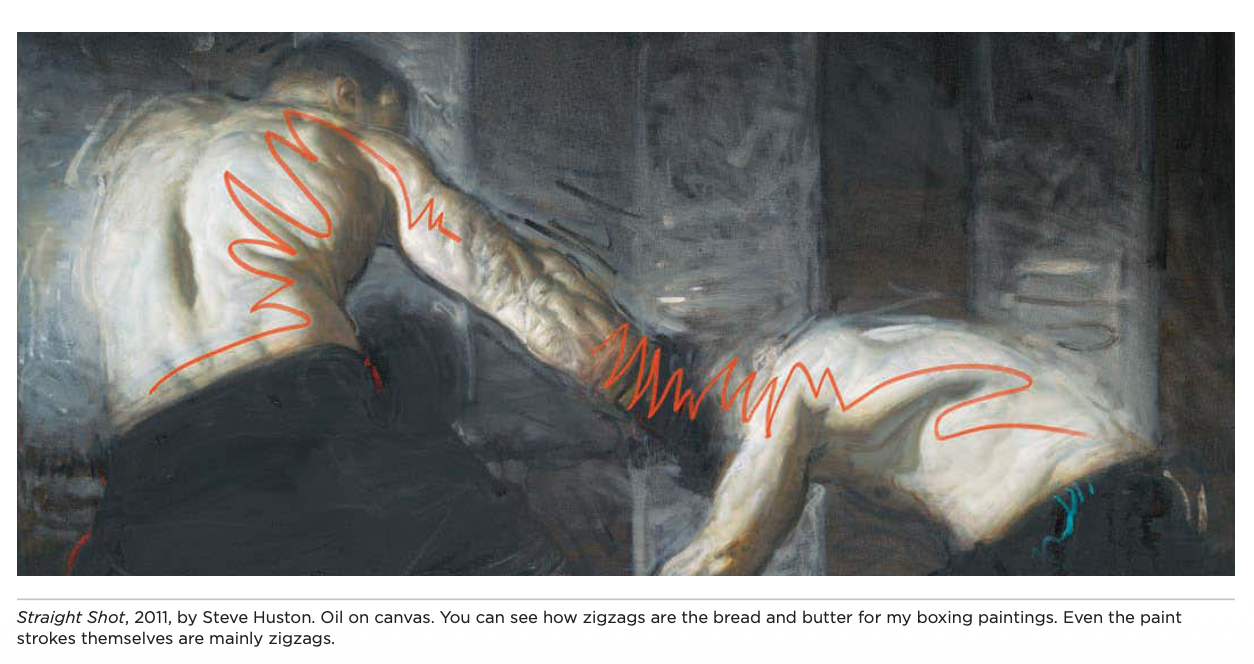

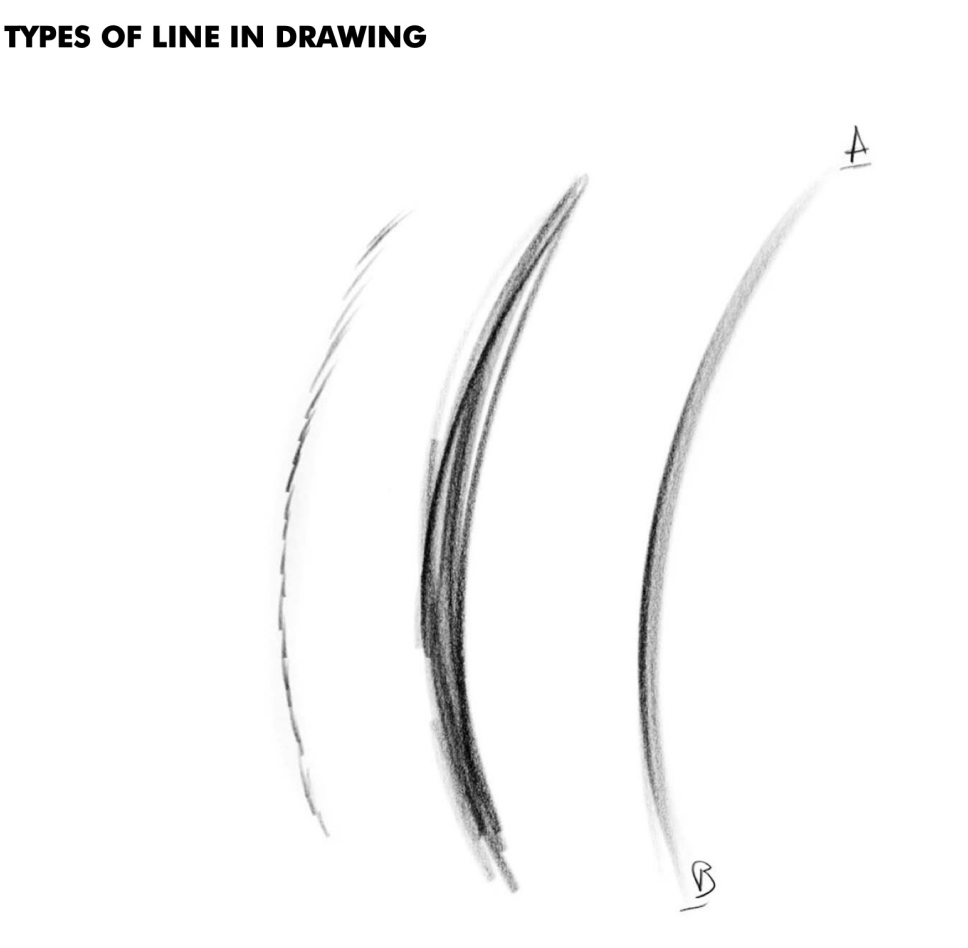

If drawing is a language, line quality is the vocabulary. By manipulating how we draw a line, we change what we communicate. This involves three primary dimensions: path, weight, and edge.

First, consider the path and flow. A confident, continuous line conveys speed and sleekness. These are the silent heroes of a drawing, providing structure without distraction. Straight paths provide stability for architecture, while curved lines offer the organic movement found in living things. Short, sketchy lines often called "hairy lines" when used by beginners can serve a vital purpose for the master, capturing vibration and the softness of a form.

Mattesi, Michael D. FORCE: Dynamic Life Drawing: 10th Anniversary Edition. 3rd ed., CRC Press, 2017. https://amzn.to/49yndU9

Second, we look at weight and value. Line weight refers to thickness, which is a primary tool for creating a visual hierarchy. Thick lines appear to advance toward the viewer and suggest shadow, while thin lines recede. Similarly, shifting from light to dark values allows you to establish atmosphere and lighting without ever using a shading tool.

Michelangelo use of varying line weight to capture form and depth! Michelangelo, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (around 1510-11)Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (24.197.2 recto)

Finally, consider the edge and texture. A hard edge provides a crisp, clear boundary, perfect for man made materials and focal points. A soft edge blurs into its surroundings, creating the atmospheric haze needed for skin, clouds, or distant horizons.

Application I: The Discipline of Design

When we focus on design, we are less concerned with realism and more concerned with the arrangement and rhythm of the two dimensional surface. In this discipline, the line is used to manage the flat space of the page.

Even if you don’t appreciate abstract works of art. I think it is important to take a moment and appreciate how these works of art expand our visual vocabulary.

Franz Kline, Untitled, 1957. Oil on canvas, 79 x 112 1/8 inches. Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery. © 2025 The Franz Kline Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

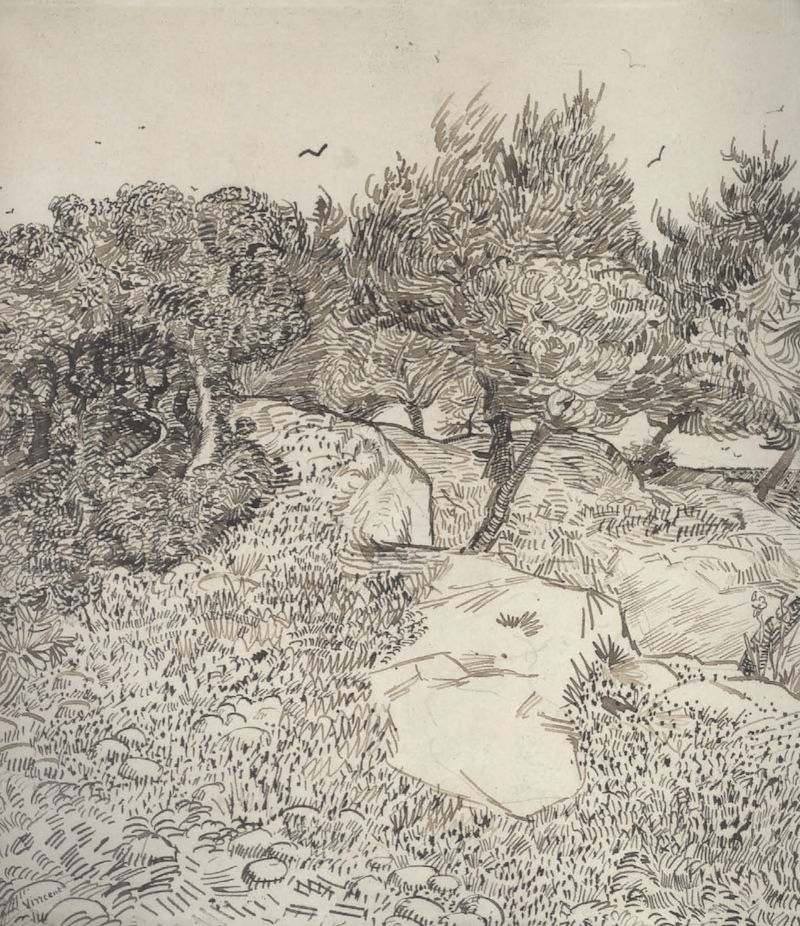

One way this works is through partitioning space. A line does more than describe a subject; it divides the paper into positive and negative spaces. Effective design ensures that the empty negative space is just as visually interesting as the positive shapes. Design also relies on the silhouette to create a clear "read." A strong silhouette allows a viewer to identify an object instantly, even without internal detail. Furthermore, by repeating lines with specific qualities, we create decorative patterns and motifs. This is the basis of textiles and graphic branding, famously seen in the deliberate, rhythmic marks of Van Gogh’s drawings.

Van Gogh, Vincent. The Harvest (for Émile Bernard). 1888, reed pen and ink on paper, 31.8 x 24.1 cm. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

Application II: The Discipline of Form

If design is about organization, form is about deception. The goal of this application is to trick the human eye into seeing depth, weight, and volume on a surface that is actually flat. Here, the line becomes a structural tool.

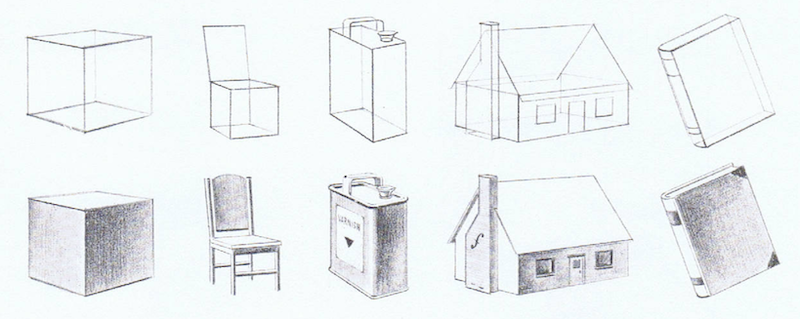

Famous Artists Schools. Famous Artists Course: Lesson 2, Form. Famous Artists Schools Inc., 1960.

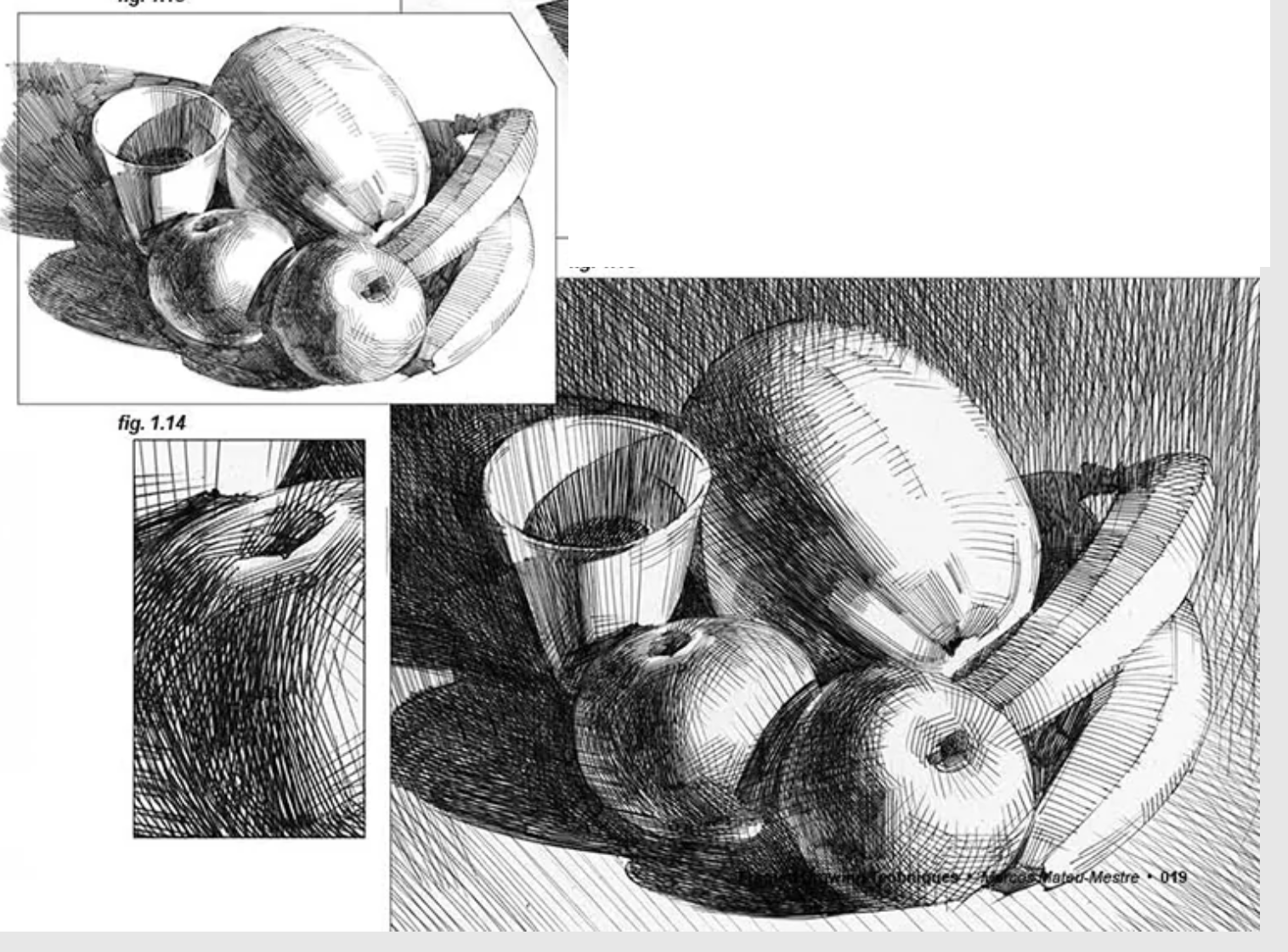

Artists use cross contours, which function like the "ribs" of a drawing. By drawing lines that follow the terrain of an object, like a rubber band wrapped around a cylinder, you define the object's volume. Linear perspective provides the mathematical use of the line, aiming marks toward a vanishing point to mimic how the human eye perceives distance. Finally, form is defined by light through hatching and density. By increasing the number of lines in a specific area, you create value, giving an object the appearance of being hit by a light source.

Mateu-Mestre, Marcos. Framed Drawing Techniques: Mastering Storytelling Through Graphic Design. Design Studio Press, 2019. https://amzn.to/4bfEZNf

Combing the magic!

Even though we should study each part separately, so we can have a deeper understanding of the specifics. The hallmark of a seasoned artist is the ability to satisfy both design and form simultaneously through line economy. As mastery grows, you learn to execute a single, elegant stroke that defines a beautiful, flat design shape while simultaneously utilizing varying line weight to suggest the volume of a form.

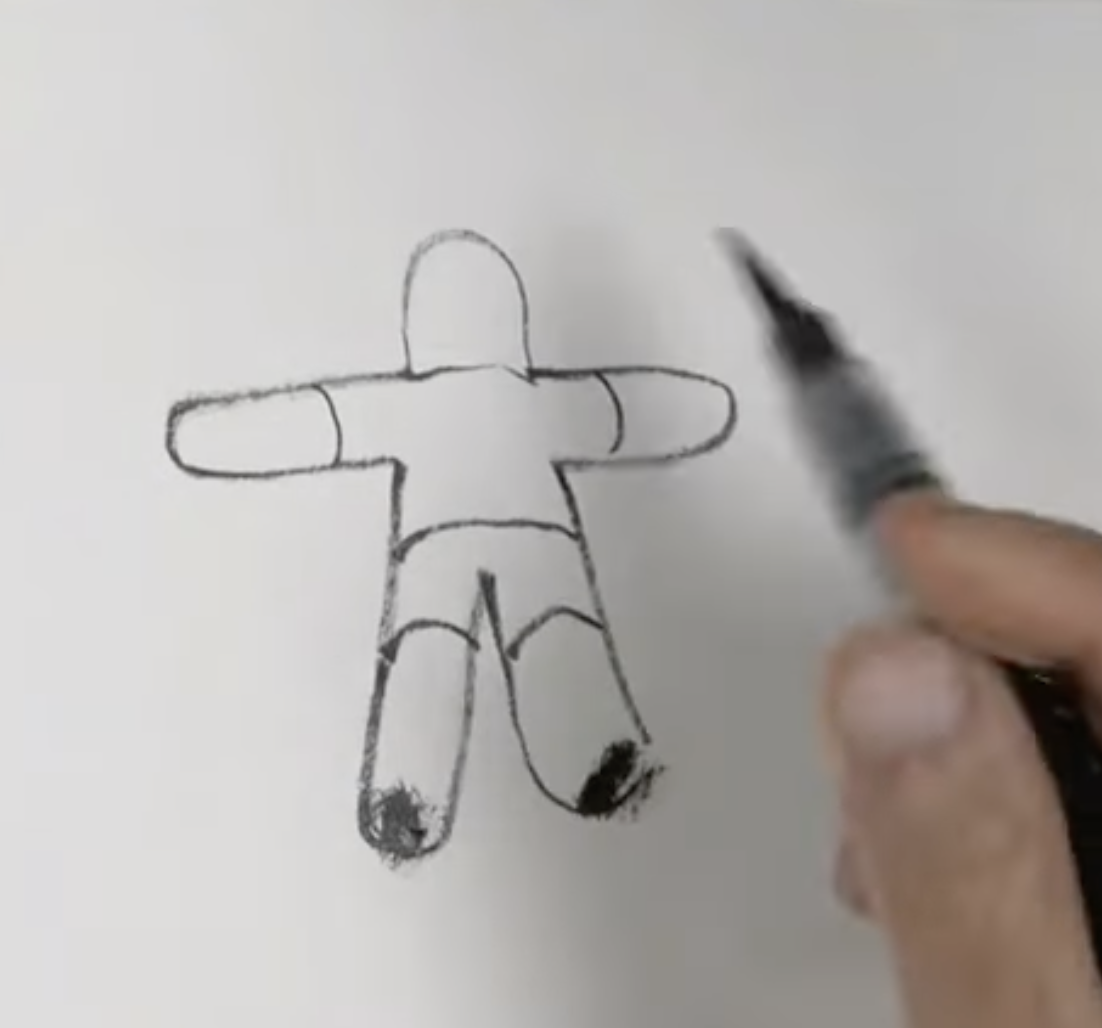

Kim Jung Gi Demonstrating how to turn a Simple 2D shape into something with form!

Form, body, structure-- Trial class-From the series【100 Lessons Kim Junggi】https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztt22A_takM